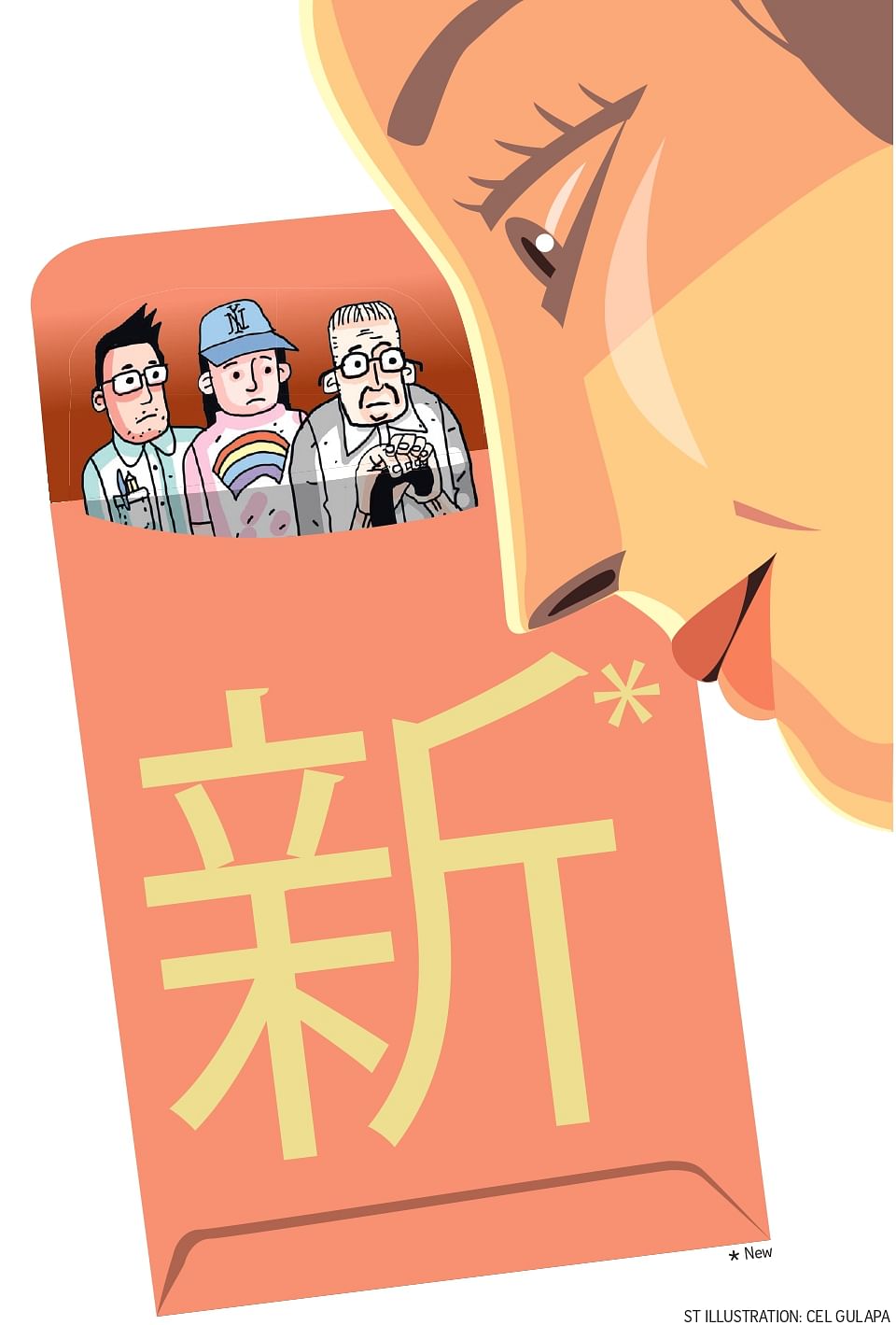

Chinese New Year ‘market rates’ and giving hongbao after you marry: Time to update traditions?

How about giving red packets when you start working or surrendering the practice when you retire?

If you are the sort to dread Chinese New Year celebrations, you are not alone. Family gatherings can be wonderful, joyous, yet rife with stress – all at the same time.

Singles are pestered about when they will get married and newlyweds badgered about their childbearing plans. For children, there is the pressure of comparing grades. In adulthood, there are questions about one’s career. All this against a backdrop of red packet gifting, which comprises yet more conundrums.

How much should hongbaos contain? At what age, if one is still single, does it become awkward to keep receiving them? What do you do when red packet gifting becomes a financial strain?

It is no surprise that some have replaced yearly family visits with an overseas trip to get away from it all.

In keeping with the times, perhaps a refresh of hongbao traditions is due.

Do away with rate guides

As a newlywed giving out red packets for the first time, I cast about for reasonable amounts to gift and was surprised to discover that numerous websites publish “market rates” online.

I’ll be honest – I baulked.

Financial website Seedly, for instance, recommends $288 to $888 for parents, in-laws and grandparents, $58 to $288 for siblings and $10 to $28 for cousins, nieces and nephews.

Even the average sum for each category comes up to between $1,500 and $2,500 per person, depending on the size of one’s extended family.

It is a pretty penny, especially for young couples also paying for a new home and its accompanying renovations. Throw in the gloomy financial outlook of inflation, an impending recession and this year’s goods and services tax hike, and these figures loom even larger.

As anyone who has ever been to a Chinese wedding banquet will agree, red packet market rates chafe. Gifting should not come with obligations, especially when hongbaos are meant to symbolise a blessing.

And though rate guides come with the caveat that one should give within their means, it is more difficult to do so when the receiver already has expectations in place.

Over the years, whenever The Straits Times reports on hongbao going rates, it is accompanied by a unanimous chorus of interviewees saying “it is the thought that counts”.

Since that is the case, let us put our money where our mouth is and encourage gratitude, rather than comparison.

Gifting should begin when one starts working

Chinese culture dictates that couples should give out hongbao when they get married, as it is an indicator of adulthood. But with people getting hitched later in life, perhaps this no longer applies.

The median age of first marriage was 30.5 for men and 29.1 for women here, reported the Singapore Department of Statistics in 2021, up from 10 years ago.

And marriage is not an option for the LGBTQ+ community – about 12 per cent of the population, according to a 2022 Ipsos survey.

Then there are those like J, 38, who has been in a relationship for 13 years and does not intend to get married. But she faces uncomfortable questions about it each Chinese New Year.

“I really dislike receiving hongbaos when they are from old-school relatives saying, ‘I hope this is the last year I’m giving it to you.’ It feels like shaming people who actively choose not to go down the institutional route of marriage,” she says.

She gives red packets to her parents and older unmarried relatives who took care of her when she was younger, a practice she began six years ago.

A, 35, does the same as a form of respect. She is in a seven-year relationship with a woman, although most of her relatives regard her as single.

She says: “I started doing this five years ago when I was working and they saw me as an adult. There was one year I realised my pay had increased, and I could give back.”

A more equitable approach to hongbao gifting would be for it to kick off when one starts working, similar to the practice of giving green packets during Hari Raya Puasa.

After all, this is when most people start giving money to their parents, either to supplement the family income or as a form of appreciation for their years of care. The amount need not be large, but a token sum to celebrate a coming-of-age.

Let retirees opt out

If giving hongbaos is linked to employment, then it only makes sense to stop when one retires. If you have children, they are likely to be grown up and giving out hongbaos of their own.

My uncle, in his 80s, informed the family about five years ago that he would stop giving out hongbaos.

A sensible move. For many, retirement comes with prudent financial choices to cushion one’s golden years.

And if there are well-heeled retirees who want to keep doling out the dough, I am sure none of their relatives will begrudge them.

Dear reader, do not fear the loss of tradition. Think of this as an update, just as how banks now encourage “fit-for-gifting” instead of new hongbao notes to reduce carbon emissions, and digital hongbaos have caught on.

It is this generation’s bid to weave environmental sustainability into a well-loved holiday, keeping it alive for the next. I have ordered my QR hongbaos from DBS Bank, and have friends who are doing the same.

But holidays do not thrive merely because of ample resources – they do because people believe in them, and feel that they are relevant. The meaning of the celebration must be aligned with society’s values, which in this day and age lean towards being equitable and caring for those who have less, rather than material excess.

J, from earlier, recalls Chinese New Year celebrations in Malaysia as a child, where it was common to receive a sum like RM1.20 from her relatives. In hindsight, she says receiving less than her friends in Singapore made her appreciate Chinese New Year for family ties, instead of for the money. The same practice, yet so much more meaning.

What if we did the same here? Perhaps a refresh of old rituals would shift the focus on Chinese New Year back to its core. Perhaps this might welcome those who dread the celebration back into the fold, and make the season warmer for the rest of us. Perhaps we might even enjoy giving out hongbaos, instead of doing so as a matter of expectation.

After all, while Chinese New Year norms have evolved, the significance of the season has never waned – even as we adapted to (and, dare we say, enjoyed) pared-down pandemic celebrations over the past two years. It is still a time of family, togetherness and feasting that many look forward to.

As celebrations ramp up again, let us be flexible with traditions, giving leeway to ourselves and others to interpret them in a way that feels right. This, to me, seems the best way to have them live on.

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

No comments:

Post a Comment