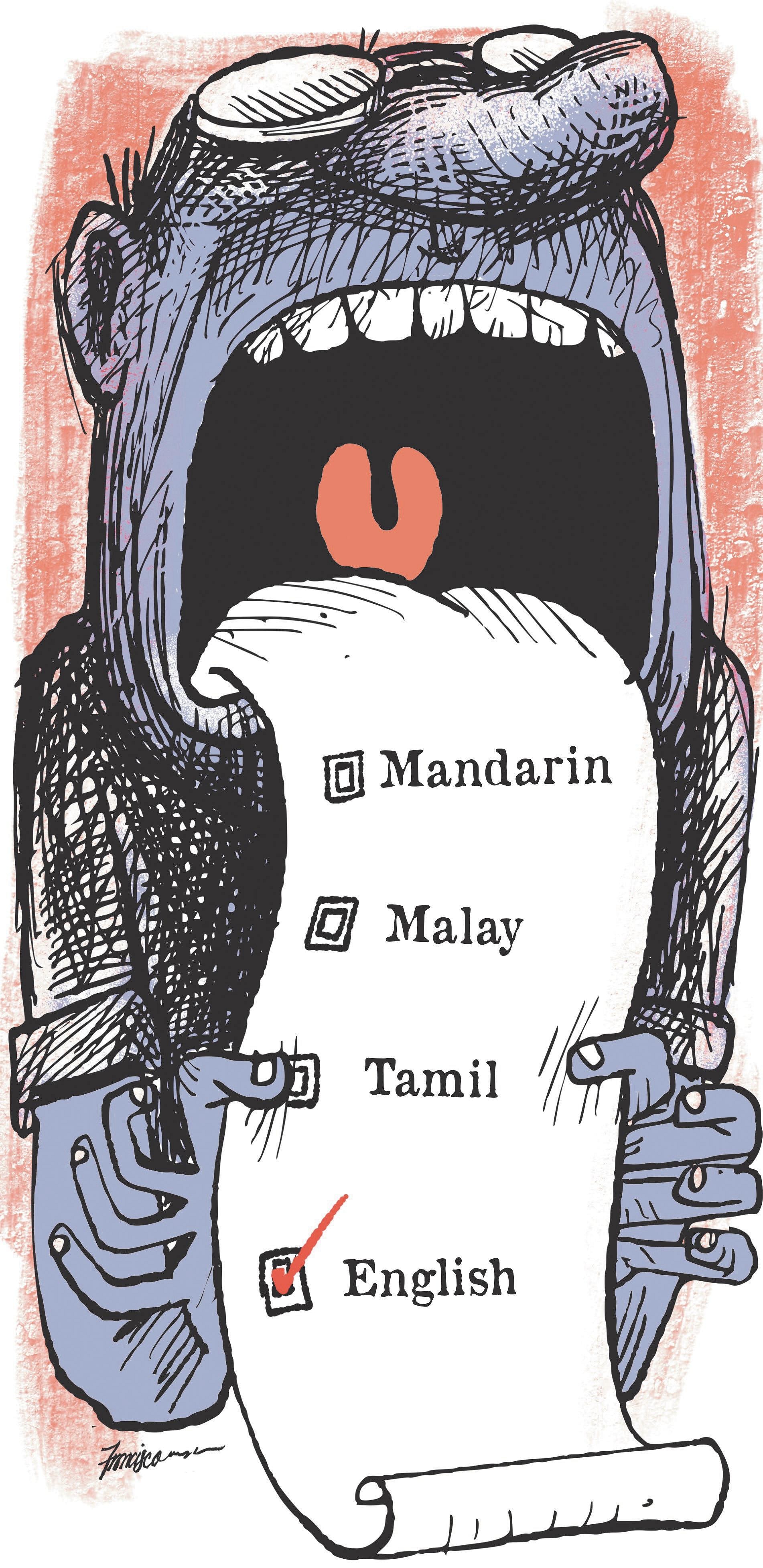

Must you speak English to qualify as a Singapore PR or new citizen?

The relationship between language and the Singaporean identity should be considered as we navigate concerns about immigration

Is English proficiency a suitable litmus test for Singaporean citizenship?

Debates over this question have swirled this week, following Leader of the Opposition Pritam Singh’s proposal in Monday’s Parliament sitting to include English language testing in assessment criteria for Singapore citizenship or permanent residency.

Second Minister for Home Affairs Josephine Teo responded with surprise and expressed concerns over the potential punitive outcomes. In particular, individuals less proficient in English but with legitimate family ties, such as foreign spouses or dependents, could be hindered from obtaining citizenship or residency.

English, Singlish and being Singaporean

On the surface, Mr Singh’s argument has merit and should not be summarily dismissed. Many Singaporeans deem English language mastery an essential component of being Singaporean.

A 2021 report by the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) on the Making Identity Count in Singapore survey involving around 2,000 respondents found that more than nine in 10 viewed English as “very important” or at least “somewhat important” to their identity.

This is both a reflection of the population’s language competencies and a function of social identity. As with many things in Singapore, including infrastructure, GDP per capita, and living costs, our English standards come close to the top of worldwide rankings.

Though not usually perceived globally as a top-of-mind Anglophone country like the United States, Britain, Canada and Australia, a 2022 English proficiency index ranked Singapore second in the world behind the Netherlands, out of 111 non-traditionally-Anglophone countries.

As the official working language, the value of English is magnified for non-Chinese minorities. Proficiency in English endows them with a common linguistic denominator in Singapore and a level playing field to access services, connect with others regardless of race, engage with the broader community, and thrive at work.

Our embrace of Singlish does not seem to detract from the spotlight on English either. Singaporeans are generally confident in code-switching between vernacular languages depending on context, even though using Singlish has long been seen as antithetical to sustaining national mastery of standard English.

A separate IPS study involving over 4,000 Singapore residents in 2018 found that over nine in 10 respondents who identified strongly with Singlish, also indicated similarly high degrees of oral proficiency in standard English.

English, as Singapore’s lingua franca, is also a significant pillar of the twin-barrel identities we embody – Singaporean Chinese, Singaporean Malay, Singaporean Indian.

Another 2017 IPS survey on ethnic identity in Singapore notes that nearly eight in 10 of over 2,000 respondents across all ethnic groups felt that speaking good English was important for those with this hyphenated identity.

Citizenship tests and their challenges

But Mr Singh’s suggestion to impose barriers to entry for immigration through some form of standardised testing is not novel. Many countries like the US, Canada and most European Union states require potential immigrants to clear proficiency tests in official languages used.

Other tests involve querying an individual’s civics knowledge on the assumption that familiarity with a country’s history, government, laws, customs and values are accurate predictors of one’s commitment to the path of citizenship and their capacity to integrate.

However, such standardised tests have several limitations. They measure a narrow range of knowledge and skills, and often reward individuals undertaking rote memorisation and superior test-taking strategies. In the context of citizenship, they may not reflect an individual’s ability to apply principles or skills in real-world settings.

The bias against and extra barriers to entry posed for well-meaning, prospective new citizens with strong family ties here but lack the requisite language proficiencies, literacy skills, or access to resources to clear standardised testing requirements, should not be underestimated either.

Such individuals can still contribute productively to or support Singapore society through their valuable tradecraft, or their role in the household as the spouse or dependent of a Singaporean or another new immigrant.

The nature of integration as an ongoing process is another factor rendering one-off testing less effective at measuring propensity to integrate, or encouraging new citizens to integrate. This sustained ability to integrate – a function of one’s actions, intentions and objectives – cannot be measured by tests of knowledge.

Singapore’s immigration regime and the way forward

Rather than rely on citizenship tests as prerequisites for citizenship, Singapore’s current emphasis has been to aid potential immigrants to live out their choices to be Singaporean.

Aspiring new Singaporeans must complete the Singapore Citizenship Journey (SCJ) programme before obtaining citizenship. The SCJ comprises several community-sharing sessions and experiential visits which aim to cultivate a better appreciation of Singapore’s history and culture.

Another e-Journey component requires citizenship applicants to complete a seven-chapter, 2.5-hour online course spotlighting Singapore’s shared values, citizen responsibilities, and social norms. Seven mini-quizzes help reinforce the content and ensure participants stay engaged throughout the course.

In 2020, the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth (MCCY) convened a Citizens’ Workgroup for the SCJ to encourage more discourse on “What Makes Us Singaporean”. The inputs from this workgroup informed the current version of the SCJ.

The convening of this workgroup on a regular cycle, rather than on an ad-hoc basis, will enable prevailing concerns to be reflected and tackled in a timely and relevant fashion.

Another option is extending a portion of the online e-Journey component to permanent residency applicants. Familiarising these individuals with key institutions, values and norms in Singapore will facilitate their integration into Singapore society especially if they become new citizens down the line.

Most importantly, the involvement and buy-in of Singaporeans are vital resources required to inform, iterate and improve the immigration regime.

This can take the form of being involved in integration programming – building friendships with new immigrants, helping them to understand the nuances of Singlish, or volunteering as Integration and Naturalisation Champions in People’s Association efforts to help new immigrants settle in Singapore.

The above are potential pillars to helm a more meaningful, less “gameable”, and longer-term approach to enhance new immigrants’ understanding of Singapore’s diverse social fabric and build meaningful bonds between locals and new immigrants, compared with one-off standardised testing.

Concerns about immigration and national identity

Singapore presently enjoys a comprehensive and rigorous framework vis-a-vis assessing suitability for citizenship and permanent residency.

Various markers of social integration such as family ties to Singaporeans, length of residency and completion of national service are considered in the process, alongside an applicant’s economic contributions, qualifications and age.

If anything, the recent debate has exposed the ground realities of a city-state seeking to balance economic, social and cultural considerations, and sustain its social compact with 15,000 to 25,000 new citizenships granted annually over the last decade.

Singaporeans generally accept the need for immigration for continued economic vibrancy, given our low birth rates. New citizens and permanent residents mitigate our ageing, shrinking population, sustain productivity and competitiveness in value-added industries, and enrich our culture with perspectives and practices in line with our identity as a nation of, and built by, immigrants.

Over three-quarters of respondents to the 2021 study on national identity agreed immigrants were generally good for the economy, and six in 10 felt immigration strengthens cultural and ideological diversity.

But we also harbour various concerns about migrants, ranging from increased job competition to the dilution of local culture and increased social divisions. The 2021 World Values Survey polling over 2,000 Singapore residents found that about four in 10 agreed that immigration leads to social conflict and precipitates unemployment.

Today, Singapore has a wide range of policy measures to check such threats of unfair competition – quotas on work permits, an emphasis on building a Singapore core in the workforce, and generous subsidies for Singapore workers to upskill and remain competitive in the labour market.

Efforts to ensure migrants entering Singapore complement rather than compete with the local workforce, and can grow the economy, have also been under way, with new conditions imposed on foreign visas like the Global Investment Programme (GIP).

Political leaders are also making concerted endeavours to highlight the positive economic spillovers of sustaining Singapore’s openness to quality foreign talent.

Just last week, Minister of State for Trade and Industry Low Yen Ling highlighted that the GIP generated more than $5.46 billion in total business expenditure via direct investments from 2011 to 2022 and created over 24,000 jobs in the city-state.

The crux of the matter, though, lies in managing the social challenges of immigration, including cultural erosion and exacerbation of social divisions, as alluded to by Mr Singh.

Moving forward, immigration policy must certainly give heavier weightage to the ability of individuals to integrate and establish roots here. But this should be effected with an eye on inclusivity and the diverse attributes of the local-born citizenry.

While English language testing for aspiring PRs and new citizens may seem like a simple fix to ensure a baseline level of integration, it implies that those not proficient in the language cannot integrate into Singapore society.

This implication will entail reflection on the part of local-born Singaporeans too: Does a poor command of English make some of us any less Singaporean? Surely not.

A more holistic approach with longer-term programming and active involvement from local-born Singaporeans will forge a stronger and more united society, rather than the limited lens of language proficiency as a criterion for citizenship or residency.

- Mathew Mathews is head of the Social Lab and principal research fellow at the Institute of Policy Studies, National University of Singapore. Melvin Tay is research associate at the same institute. They are the co-editors of Immigrant Integration In Contemporary Singapore: Solutioning Amidst Challenges (World Scientific, January 2023).

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

![Learn About Treating Lower Back Pain [Here] Learn About Treating Lower Back Pain [Here]](https://images.outbrainimg.com/transform/v3/eyJpdSI6ImE5MWI1MDU2ZDM0NjhkYmVhNjlmNDI3MTM1MDc1OTUxZTQ1NTc5NWRjOGY0YjY4MDQ5Zjg1YTYxZjMxODJjMzkiLCJ3Ijo2NDUsImgiOjQzMCwiZCI6MS41LCJjcyI6MCwiZiI6MH0.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment