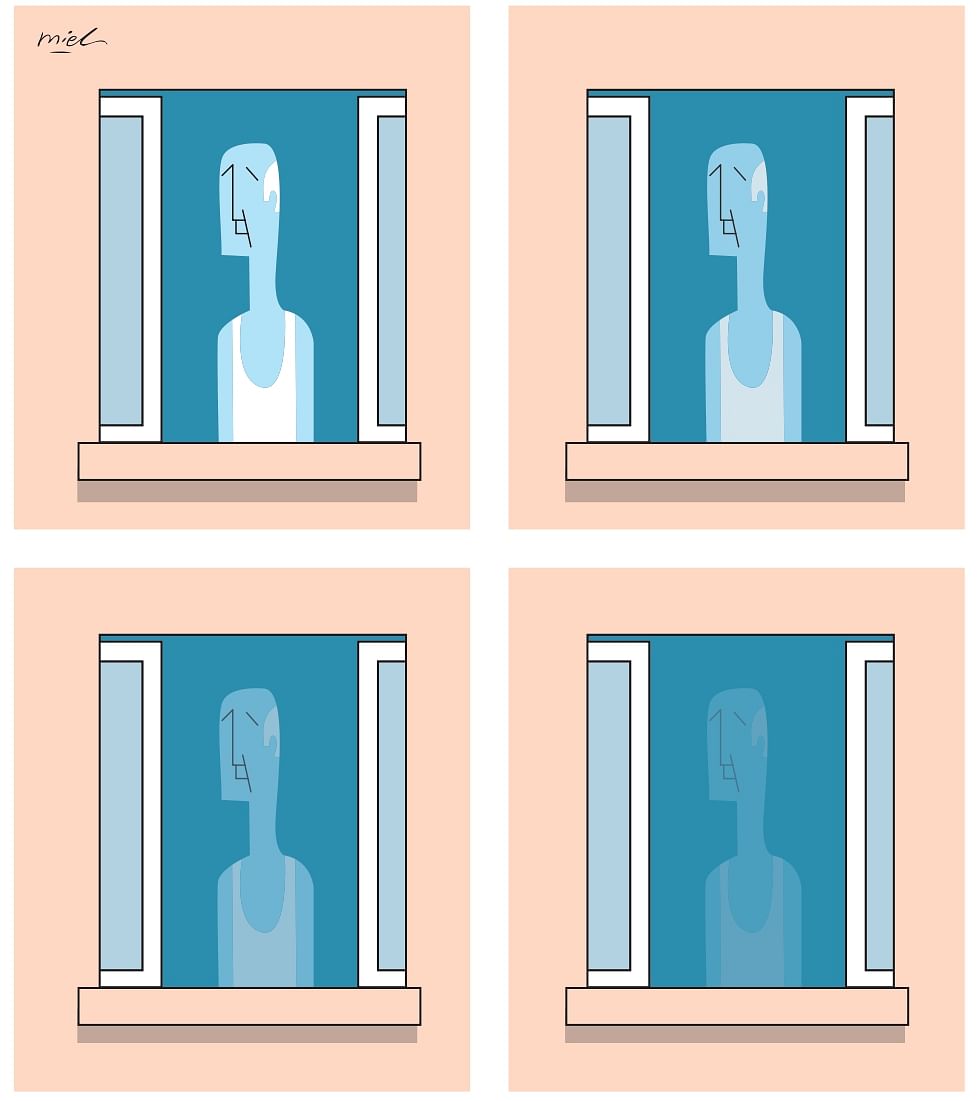

Why are S’pore’s elderly still dying alone, undiscovered for weeks?

Undetected deaths will become more salient as S’pore’s population ages and household sizes shrink. Family members and the community must look after vulnerable seniors in their midst, with technology as a useful aid.

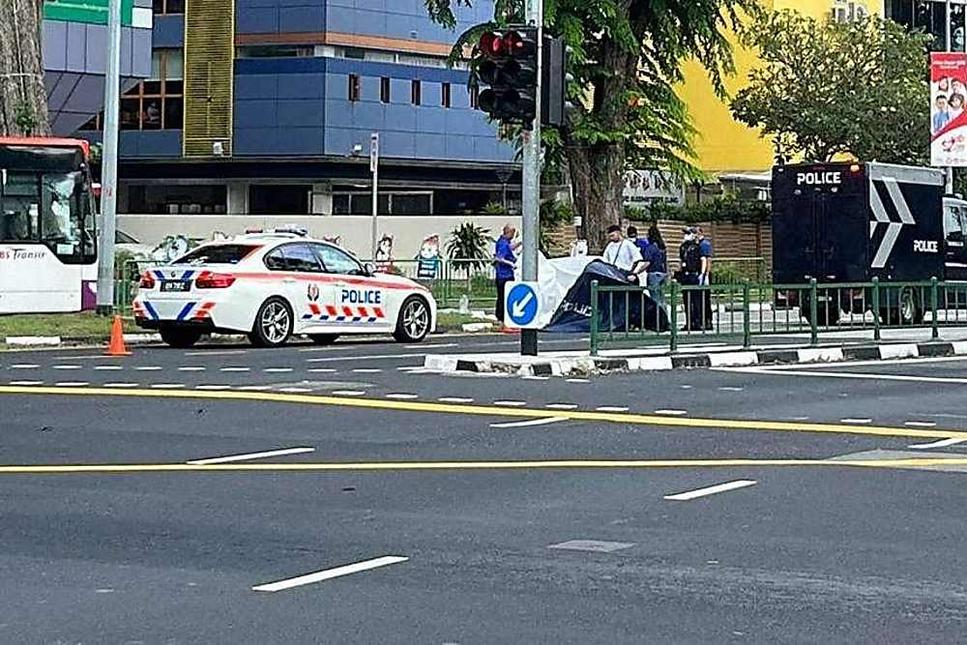

Earlier this week, a 68-year-old woman’s decomposing body was discovered in her Housing Board flat after neighbours noticed a foul smell coming from the unit.

A similar case in March involved an 80-year-old deceased woman who lived alone. “I hadn’t seen her for a week. I thought she was away and didn’t turn on the lights at night,” a neighbour told reporters then.

Other cases went undetected for even longer. In 2020, the remains of an elderly woman and her pet dog were found only after letters had piled up for months outside her condominium unit.

The issue of undetected deaths will become more salient as Singapore’s population ages and household sizes shrink, putting a strain on family support.

No doubt such incidents, while sad, are rare today.

While the Health Ministry does not track the number of elderly who die alone at home, it has been reported that the Health Sciences Authority (HSA) handles fewer than 100 unclaimed bodies each year. This isn’t even 0.5 per cent of the nearly 27,000 deaths registered in 2022.

But it cannot be taken for granted that this will always be the case.

Already, the number of people aged 65 and older here nearly doubled to 614,000 in 2020, from 338,000 in 2010. Those living alone accounted for 10.2 per cent of resident households in 2020, up from 8.2 per cent in 2010.

This ageing, solitary demographic is something which countries like Japan are familiar with. There, dying alone, or “kodokushi”, is a growing trend as fewer people get married and have children.

A similar phenomenon in South Korea is “godoksa” or “lonely deaths”, which has been exacerbated by the country’s demographic crisis and gaps in social welfare.

It’s not just death itself, but the isolation leading up to it which can kill – literally.

Researchers at Duke-NUS Medical School and Japan’s Nihon University found that people aged 60 who see themselves as lonely can expect to live three to five years fewer than peers who don’t see themselves that way.

So what can be done to minimise Singapore’s very own “kodokushi”?

Role of family

The responsibility of caring for seniors can be extended beyond their children, said Mr R. Jai Prakash, principal consultant at social change consultancy Soci.Train.

He said families should rope in other relatives, and even friends, to take turns in looking after the elderly. “It is also important to build good relationships with neighbours. The definition of family or a pseudo-family needs to be broadened.”

The frequency of contact matters. For example, family members can make it a point to text their seniors a few times a day. If they do not reply for long periods of time, it may signal unusual behaviour requiring attention.

Some frail seniors with medical conditions can wear devices that monitor vital signs, said Adjunct Associate Professor Corinne Ghoh of the National University of Singapore’s Department of Social Work.

It could even be something as simple as hanging a mobile phone over oneself with a strap so that one can call one’s children easily in times of need.

The point is to build in protective measures in one’s lifestyle so that the older person is “sighted” daily by family members, she said. “The older person can feel a sense of security, and the family members can have peace of mind.”

Community and social support

Studies show that social support is a key protective factor for older adults, helping to buffer them against stressful life events.

Prof Ghoh said that the quality and reliability of this support matters. “Even a single confidant whom the senior knows can bring down levels of depression,” she said.

What counts as a social support network? It could be neighbours, friends and interest groups, faith-based organisations and grassroots agencies, or drop-in centres like the active ageing centres (AACs), which provide befriending and other activities, as well as help with care referrals.

The Silver Generation Office (SGO) – the outreach arm of the Agency for Integrated Care (AIC) – regularly reaches out to seniors. Seniors can also subscribe to CareLine, a round-the-clock personal care telephone service.

But what if seniors refuse to open their doors or call for help?

Prof Ghoh said the community should alert AACs or the SGO if they suspect something amiss, such as not seeing the senior come out of the house the whole day.

SGO chief Sng Hock Lin told me it is impossible to predict where and when the elderly – even those who appear to be in the pink of health – could die.

This is why the “kampung (village) spirit” is so important, he said. Because the elderly are less mobile, it matters that they have friends and neighbours to call on, as well as AACs to go to in HDB estates.

“If you’ve registered at an AAC and you don’t come down for activities today, people will come up and check if you’re okay,” he added.

“People used to go to the void deck to chit-chat and build relationships. And really what we’re trying to do here is build this social connection through AACs, or even informal ones like coffee shops. It’s about having all hands on deck and helping one another.”

He said that what agencies like SGO can do, if seniors are reluctant, is to continue to nudge them to sign up with AACs while providing different levels of care.

Financial assistance also helps. To offset the cost of assistive devices such as walking sticks and wheelchairs, as well as home healthcare items like adult diapers and wound dressings, those who are eligible can apply to tap the Seniors’ Mobility and Enabling Fund.

For homebound seniors who cannot buy or prepare their own meals, the AIC and various charities provide meals-on-wheels delivery services.

Some form of “neighbourhood watch” programme also exists in other countries. In South Korea, the community pays visits to single-person households in vulnerable areas such as basement apartments and subdivided housing.

Hospitals, landlords and convenience store staff play the role of “watchmen”, notifying community workers when patients or regular customers are not seen for a long time, or when rent and other fees go unpaid.

Keeping tabs with technology

Having motion sensors connected to family members’ or community partners’ mobile apps can allow caregivers to intervene quickly in an emergency, said Mr Prakash.

Dr Kelvin Tan, the head of the Minor in Applied Ageing Studies programme at Singapore University of Social Sciences, calls for smart technology to be installed in homes.

He observed that traditional emergency alert devices have a few downsides: cords or buttons require physical activation through pulling or pressing, while wearable devices must be worn by users all the time.

However, local start-ups like Soundeye have come up with sound-activated monitoring systems which use thermal infrared and ultrasonic detectors. This allows them to detect not just falls, but also cries for help.

In April, it was reported that the Government Technology Agency (GovTech) and AIC were exploring the use of radar sensors to detect seniors falling at home.

Under the trial, about 150 seniors living in Marine Parade, Bedok South and Ang Mo Kio will be provided with free Internet-enabled touchscreen tablets. The tablets will work with radar to track any falls within their radius.

Elsewhere, Japan has pioneered care robots such as Lovot, a portmanteau of “love” and “robot”. Each Lovot’s 360-degree camera allows it to quickly locate its owner. It can also gather data on its owner’s well-being, and report it remotely to the person’s children living elsewhere.

A culture of care

Observers stressed that seniors living alone isn’t in itself a bad thing.

“We assume that seniors staying alone will be very lonely. But I’ve had seniors tell me, ‘I’m an introvert’,” said SGO’s Mr Sng.

More educated or never-married older adults may well choose to live on their own. They have spent more time in the labour force and have different expectations, said Associate Professor Angelique Chan, the executive director of the Centre for Ageing Research and Education at Duke-NUS Medical School.

The key issue, she said, is that many individuals do not make advance preparations for how they want to live in their old age.

“It may not be apparent to young adults or even those middle-aged that maintaining social connections, taking care of one’s health, and preparing financially for old age are all things that need to be done starting young.

“Once an older adult is living alone in poor health with little support, it is almost too late and non-family agents need to step in.”

A culture of care develops with time, and empathy for others begins in schools, Prof Chan added. “This then leads to developing the same culture in the workplace (and beyond) - where individuals are aware of each other and notice when a colleague is not well.”

In the end, we all have a responsibility to look out for seniors in our midst.

See a frail-looking senior with mobility issues? Uncollected mail in letterboxes? Rubbish piling up on their doorstep?

Maybe it’s time to be kaypoh (“busybody” in Hokkien) and knock on their door, offer help or alert the authorities. You could be saving a life.

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

No comments:

Post a Comment