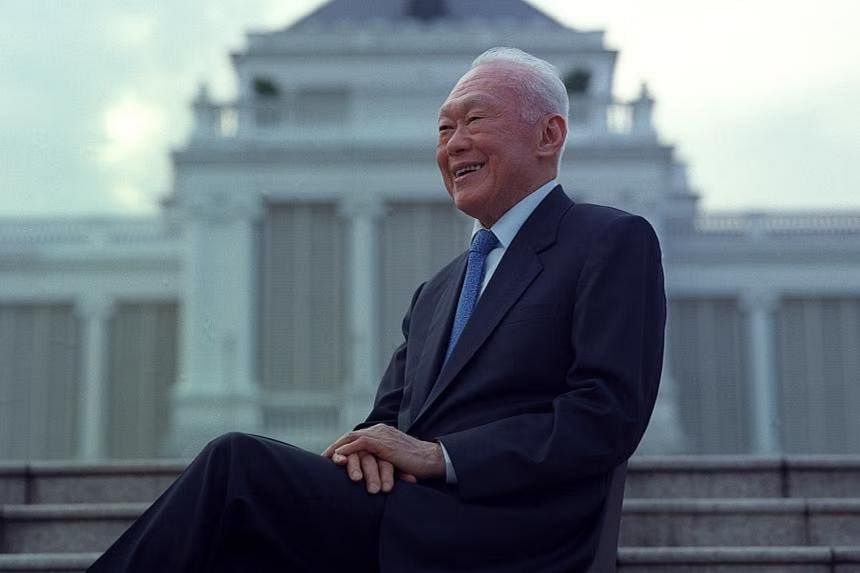

Lee Kuan Yew at 100: Taking Singapore beyond the LKY legacy

At first, he was the authoritarian leader whose “system” I loved to critique. Then I realised I was a product of that system.

My first serious assignment as a political reporter in 1991 was to check out a new book about Singapore, which was not available in Singapore but was doing a roaring trade across the Causeway in Johor Bahru, Malaysia. It was an “own” story, which meant the idea came from me, and I had pitched it to my supervisors and obtained their permission to work on it.

I travelled to Johor on a short day trip and interviewed booksellers. I rang up book distributors and stores, and interviewed readers and commentators on the book. Titled Singapore: The Ultimate Island (Lee Kuan Yew’s Untold Story), by T. S. Selvan who was then living in Australia, the book had been published in late 1990. By the time I wrote the story, it had sold over 10,000 copies in Malaysia, mostly to Singaporeans, according to the book distributor and booksellers I spoke to in Malaysia then.

The article was published under the innocuous headline, “New book on Mr Lee, govt and press doing well in JB”. It was a short, 10-paragraph article but had taken weeks to be published, with the reporting and editing process.

It was a particular thrill at that time, in the early 1990s when the People’s Action Party was extremely dominant, to report on a book critical of Mr Lee Kuan Yew. I also saw it as my professional duty as a journalist to keep up to date with and report on “dissident” views – and write about alternative perspectives on Singapore politics, even while most of my time was spent reporting on more mainstream political views.

As a young adult growing into intellectual maturity in the 1990s, I related to Lee Kuan Yew and his views the way a rebellious adolescent raised in a traditional Chinese family may engage with the distant male authority figure in the family: With a mix of surface deference, huge amounts of scepticism and a thinly veiled disdain for authority.

He was the father figure to the nation, which my young imagination conjured into a dictatorial figure, the foil to my emerging democratic political consciousness. My friends and I spent hours critiquing “the system” – the catch-all phrase that referred, darkly, to the way Singapore operated – its political system, its efficient if intrusive public policies, the way tight networks of institutions and individuals were wound together.

Then I joined The Straits Times as a political reporter. Mr Lee was shorn of metaphor and myth, into a person I met in the flesh. I covered Mr Lee at many constituency events, and years later, on official trips overseas. I eventually became part of a team of journalists who interviewed him for a series of books on his views on Singapore and the world. From critiquing the system, I soon realised I was part of it, as a member of the mainstream media whose job is to report on government policies and analyse them.

Over the decades, my view of Mr Lee shifted from seeing him as an authoritarian leader, to admiring him as the architect of modern Singapore, and finally watching as he aged into a frail old man still resolved to pass on his ideas to a young generation of Singaporeans – a transition I wrote about in an essay the week he died in 2015.

A few incidents from my interactions with him over the decades book-ended those shifts.

Shanghai encounter: Realisation dawns

I recall the moment I felt Mr Lee’s approval and had the niggling sense that I had become a model of what he and his colleagues had fought for.

The year was 2004, and I was accompanying Mr Lee on his visit to China, during which he visited Suzhou to mark the 10th anniversary of the project to build a Singapore-style township in China. Mr Lee sent for the Singapore media delegation to meet him during a lull period, as he wanted to hear views on China from the Singapore reporters based in Beijing or Shanghai.

I recall a meeting in his suite, reporters seated around a rectangular table. In front of Mr Lee was a dossier, which he opened and flipped through as we introduced ourselves. To one correspondent who had studied at a Scottish university, he asked in puzzlement, why did you choose that university? She replied that it had a strong programme in publishing which she was interested in.

To another reporter who came from a top girls’ school in Singapore, he remarked that she had not studied Chinese at first language level but only as a second language and that her command of the Chinese language could not be very good.

As he went round the table, he had a few candid remarks to make on each person’s curriculum vitae. Then he came to mine, and he scanned the document, and flipped the page silently.

In that brief instant, I had a flash of insight into how someone like him might view someone like me. I imagined what lay on that page: My academic background as a recipient of the Overseas Merit Scholarship awarded by the Public Service Commission, which had taken me to his alma mater, Cambridge University in the United Kingdom. My recent master’s degree in public policy from Harvard University.

He and his colleagues had fought for an independent Singapore based on equality, founded on meritocracy. In their vision of Singapore, neither race, nor gender, and certainly not social class, should hinder any person’s chances of creating a good life for themselves.

And there I sat, across the table from him in a posh hotel in Shanghai – the hawker’s daughter who spoke only Teochew when she was in Primary 1, whose parents were barely literate immigrants from China (my father had six years of education, my mother one month), who had somehow made it to Cambridge to study English literature and write essays on Shakespeare and even won a prize for a paper on Hildegard of Bingen and the mediaeval women mystics.

He was the chief architect of Singapore – the man whose policies shaped generations of Singaporeans. My life had been transformed because of the meritocratic scholarship system, and I had been given opportunities beyond my parents’ wildest dreams.

I realised that far from being a critic of the system, I was very much a product of it; indeed even a model example of what it offers. There are thousands of Singaporeans like me, working-class folk who succeeded professionally with scant social networks and without financial reserves. This is one of the strengths of Singapore’s “system” and one reason why so many Singaporeans are passionate about enhancing social mobility.

As I overcame my adolescent dislike of authority, I stopped seeing Mr Lee as the mythical fearsome leader. I saw him more clearly as the man who shaped Singapore into what it is today; and I understood better the trade-offs he and his team made to propel Singapore into a better future.

For example, the Keep Singapore Clean and Green campaign with its fines for littering and spitting was a quick way to get working-class immigrants to change their social habits quickly, in order to create a more pleasant public environment for all. As he wrote in his memoirs From Third World To First, if policies like that made Singapore a nanny state, he was “proud to have fostered one”.

And in the last decade of his life, as he spent hours with a team of ST journalists talking about his views for a series of books, I grew to see the common humanity in him.

The meditator

A third image of Mr Lee comes to mind. In one of the interviews at the Istana for the books on Singapore, the ST team had Mr Lee talking about religion, faith and views on life. He spoke about his introduction to meditation, and how he had found it a useful practice, and mused that it would be handy in school settings for students.

In separate interviews around that time, he said he meditated using the mantra word Maranatha – an Aramaic word meaning “Come, Lord”. Although he was not religious, he found it soothing to meditate using that word.

Coincidentally, I was also meditating using the same method, which I had come across when I made contact with the Christian meditation movement in the early 2000s, to help me cope with treatment for cancer during that period. When I wrote about my cancer experience in 2003, he showed a softer side, writing me a note of sympathy, offering his best wishes for my recovery, and saying he looked forward to more of my writings.

During the years when we interviewed Mr Lee for the books, when I struggled to bridle my mind in my own meditation practice at home, I sometimes thought of Mr Lee intoning Ma-ra-na-tha, trying to still his mind. Knowing that he too struggled was oddly reassuring, and I would return to my own practice.

In one of the interviews for the book Lee Kuan Yew: Hard Truths To Keep Singapore Going, he spoke about the challenges of caring for his wife Kwa Geok Choo, who was bedridden after several strokes. He would spend his evenings by her side, reading her favourite poems to her, sharing the news from The Straits Times, or updating her on family matters.

I watched the subtle play of emotions flit across his face, and looked at his hooded eyes. I heard the cadence in his voice as he spoke about mentally preparing himself for the day when she would be gone and the big house would be empty without her.

Empathy washed over me. He was no longer Lee Kuan Yew the formidable leader or the architect of a nation. He was an old man who loved his wife and was valiantly caring for her in her final months. We were bound by a common humanity – the political leader in his waning years, and the group of journalists clustered around him, witnesses to his vulnerability.

Beyond the legacy

This week marks the 100th anniversary of Lee Kuan Yew’s birth. His life shaped Singapore. It transformed mine, alongside millions of other Singaporeans. I trawled through my memories of these interactions to share the above, because I think they reflect what my generation felt about him.

Many of us grew up with images of Mr Lee as an ogre-like figure, fierce, prone to jailing his opponents. Then as Singapore politics changed and our own understanding matured, we began to understand the merit of Singapore’s way of doing things.

Many of us would cheer Singapore’s efficiency, clean government, social cohesion and public safety. We may criticise the extremes of some policies in the early decades, such as the overemphasis on development that destroyed heritage too fast, and the emphasis on self-reliance that left some struggling to fend for themselves in the marketplace. But overall, we would say, Mr Lee and Singapore got many things right.

And then, as Mr Lee stepped down as prime minister, taking on advisory roles while remaining in the public eye, we would have had to recalibrate our image of him as he grew frailer, his gait became less steady, his gimlet eyes less penetrating.

He became more reflective, declining to comment on pressing issues of the day, saying it was up to younger leaders to pick up the baton and carry on, and instead spoke about love, family and life.

My generation – those of us born in the 1960s – are now stepping up to helm national institutions. The so-called 4G or fourth generation of political leaders, are my peers or just slightly younger. Some came from the same Housing Board heartland background that most Singaporeans grew up in. A few went to the same school or university as me.

Their lives were transformed by Mr Lee’s policies. They would have had far closer and more meaningful interactions with Mr Lee than me. They would feel much more deeply, more viscerally, the responsibility to carry on with his legacy.

While doing their best to preserve the best of Mr Lee’s legacy – a successful, vibrant Singapore built on equal opportunity and meritocracy – their challenge is to also look beyond Mr Lee and push Singapore beyond the limits of that legacy. Mr Lee, after all, had human vulnerabilities: He was wrong on some issues, and some of the policies he advocated did not turn out well – for example, schemes to get more educated women to produce more children.

The centenary of his birth may be a time for commemoration, but this should just be a hiatus, a brief pause. Mr Lee of all people would have been the first to chide Singaporeans if they lingered too long in commemorative mood. He was wont to say, do not let the grass grow under your feet.

So, on Sept 16, 2023, let us pause to mark the birth of a remarkable man whose life changed my life, as it did the lives of millions of other Singaporeans. And then let us look coolly at Mr Lee’s legacy and systematically review what should be kept, what updated and what should be dismantled.

Mr Lee was also the one who said: “I’ve lived long enough to know that nobody settles the future of his country beyond more than a decade or so of his life.”

Taking Singapore beyond Lee Kuan Yew’s legacy, in order to secure the future, would be the best way to honour Mr Lee for his life’s work on Singapore.

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

No comments:

Post a Comment