In the GEP, some of us felt like the X-Men. But not all of us were heroes

Is it just a coincidence that many children in the Gifted Education Programme feel marked by difference? In the GEP, we could be different together.

On a sleepy Saturday morning in 2002, I sat down in a classroom, in a school I didn’t attend, to take a test I didn’t know would fundamentally alter the course of my life.

With no deep awareness of its significance, a nine-year-old me would have much preferred playing on my Game Boy Color to taking the Gifted Education Programme (GEP) selection test. In spite of myself, I begrudgingly realised I was having fun answering what felt like a series of tricky riddles, number puzzles and pattern-finding games.

A few short weeks later, I was horrified at the news that I had actually got in and might now have to be transferred from my neighbourhood school down the road to one much farther away.

Having spent my first two years in primary school as a quiet, weird kid who didn’t get along with others, I had now made headway in making friends. I didn’t want to start over, I protested, as my parents tried to convince me to accept the offer.

What tipped the balance was when a classmate confronted me during recess, and bitterly told me that I didn’t deserve to get in.

Indeed, everyone had been surprised when our form teacher announced that just one kid from our class had made it, but it wasn’t the know-it-all boy who was now demanding to know how I’d cheated, or the studious girl everyone called the teachers’ pet.

No, it was I, who was notorious for not handing in homework and who had recently been severely reprimanded for throwing rocks over a construction barrier to distract the workers renovating the secondary school next door, together with my budding “delinquent” friends.

I’ll show you, I thought. That night, to my parents’ delight, I announced I would go.

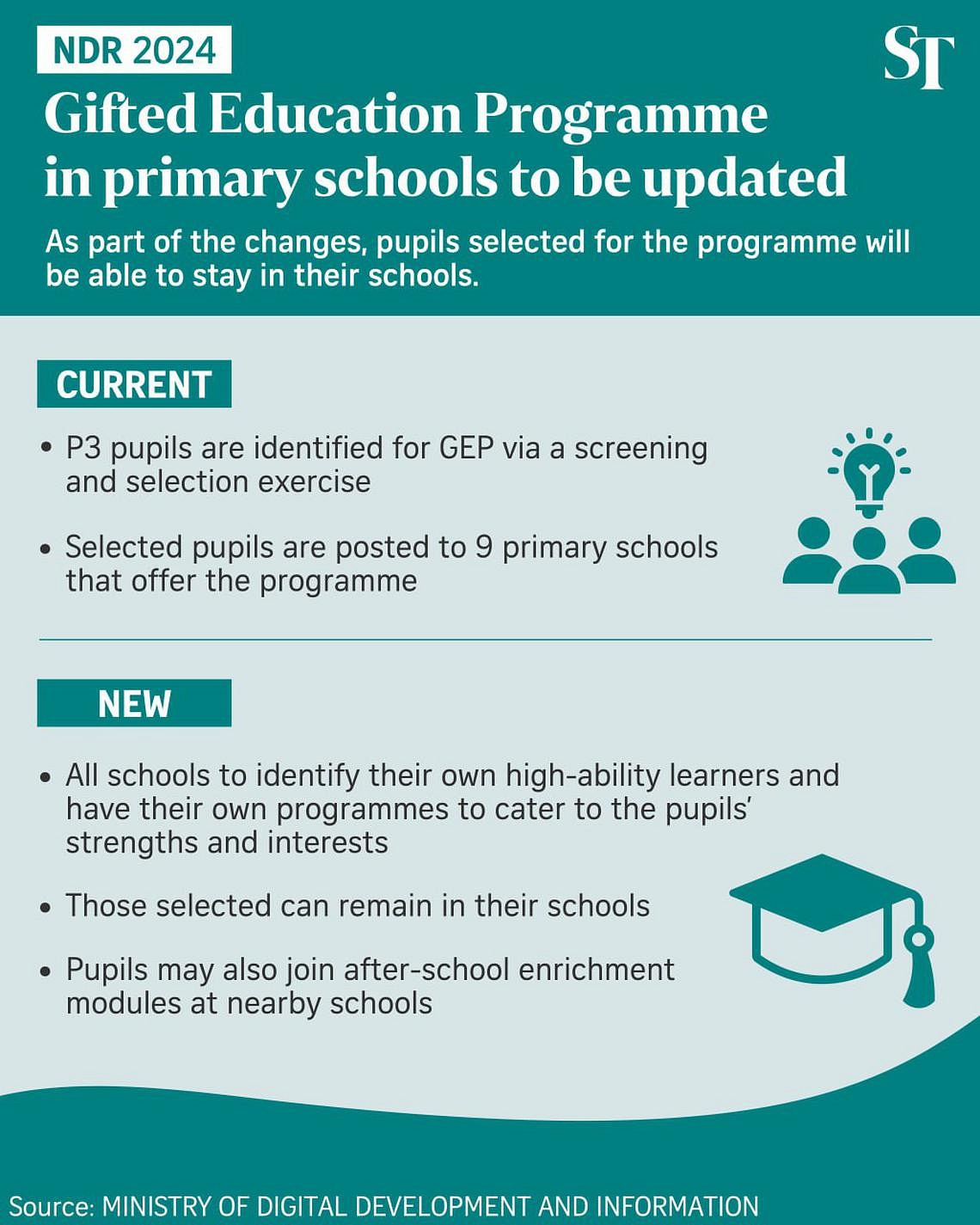

On Aug 18, Prime Minister Lawrence Wong announced during his National Day Rally speech that the now 40-year-old GEP will be discontinued in its current form.

Instead of plucking the top 1 per cent of pupils from their current schools and putting them together in nine GEP schools, every school will have its own high-ability programme for the top 10 per cent of their pupils.

As I watched the speech, I wondered wistfully how different my life would be if I hadn’t been in the GEP.

Mutants, misfits and mischief

I thought back to my favourite comic series as a child, Marvel’s X-Men, where superpowered “mutants” attend Xavier’s School for Gifted Youngsters to learn how to use their gifts for good.

Drawing an analogy to “gifted” children might seem a little on the nose. While many mutants had amazing and useful powers like flight or telekinesis, others had powers like “I kill everything I touch” or “I physically resemble a toad”. Some hated their gifts and saw them as curses, especially if they were ostracised by “normal” humans.

Being different didn’t always feel like a gift to me, either. I certainly remember, pre-GEP, being vaguely conscious of that difference and wishing I could just be normal.

My friend John (all names in this story have been changed), now a trained lawyer, felt similarly.

He said: “I felt like a robot as a kid because before entering the GEP in Primary 4, I didn’t really have any friends.”

That changed once we found each other. Some of my closest friends to this day are the kids I met in the GEP, who made me feel, for the first time, like I was among people on the same wavelength as me.

But, just like the X-Men, not all of us necessarily belonged on the main team. Many of my GEP classmates seemed to be effortlessly successful at everything they did, but while I enjoyed the enriched curriculum and my growing circle of friends, I was never going to be a model student, and I didn’t have a clue what my superpower was supposed to be.

By Primary 5, my grades were slipping badly and I was put on “probation”; I had to write reflections on how I planned to improve. If I didn’t “buck up”, I would be kicked out of the GEP.

At school, I was reminded that I was supposed to be like a speedboat among my mainstream “sampan” peers. I grew to deeply resent the constant refrains about how copious resources were being invested in me, and it was my responsibility to live up to expectations.

It started to feel like my success was not solely for my sake but more for validating the Ministry of Education’s (MOE) policies, or to uphold my parents’ bragging rights as a trophy child.

I started acting up even more. That same year, we took an after-school enrichment module called Individualised Research Study, where we learnt to design surveys and present data.

My parents were summoned to school after I decided to apply what I had learnt by conducting an unauthorised opinion poll among my classmates to support a petition I had started, calling for a certain teacher to be sacked.

I remember waiting for my parents outside the fifth-floor staffroom, convinced I had truly blown it this time and that they were going to kick me out. Thankfully, I was let off with a warning.

It later turned out that my mutant superpower was being able to do unexpectedly well on tests despite being a massive procrastinator; I could average a failing grade for three-quarters of the year, yet suddenly excel right at the end.

I continued to scrape by, completing the GEP and blundering my way into the Integrated Programme (IP) and the School-Based Gifted Education Programme in secondary school, though my rebellious streak and disruptive behaviour would persist well into junior college (JC).

‘Giftedness’ and special needs

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the parallels between “giftedness” and what we talk about as neurodivergence today. In a literal sense, a “gifted” child is merely one who thinks differently.

Anecdotally, a not-insignificant number of my GEP peers seemed to discover later in life that they had gone through school with an undiagnosed condition like attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or some form of autism spectrum disorder.

A high intelligence quotient may also be correlated with an increased tendency to overthink and over-analyse, perfectionism and burnout, as well as mental health challenges like anxiety and depression.

There seems to be a growing recognition that while most “gifted” children are socially normal and adaptable, many do have special needs and their educational outcomes may suffer if those needs are not met.

Sydney, who has autism and ADHD, recalled that many of their GEP classmates had related strongly to the neurodivergent protagonist of British author Mark Haddon’s 2003 novel, The Curious Incident Of The Dog In The Night-Time.

“It feels like everyone knew GEP had more neurodivergent kids, but we didn’t acknowledge it,” Sydney said, adding that their GEP class felt like a “much safer space” to display certain traits associated with neurodivergence, such as repetitive behaviours or tics.

Sydney identifies as having a non-binary gender and uses the pronouns they and them.

“It was so unfair that this safe space was only for people who would do well in school and on tests! It helped me so much, but I wasn’t the kid who needed the most help.”

Echoing the sentiment, Alex, who was in the GEP along with his older brother Scott, said: “We had a teacher who had written papers on giftedness, and she spoke about how gifted children were special but needed to be taught how to adapt to life in ‘normal’ society.”

“I remember how she also confessed that one of her biggest struggles was not knowing whether spare resources should be dedicated to the best or the worst students,” added Alex, who recalled that his class had so much more resources than mainstream classes.

Hank, a former GEP student who is now an MOE teacher himself, worried that there might not be enough resources to cater to “gifted” children’s needs in every primary school under the new system.

After/almost/never

Around the time I was completing JC in the early 2010s, memes and jokes about “former gifted kids” began floating around on platforms like Twitter and Tumblr.

The stereotype was that of jaded adults with stunted growth trajectories who were still burdened by the weight of unrealised potential.

Those who self-identified with the label were derided as cringeworthy and mocked for continuing to hold on to an elitist identity marker long after they had lost any right to claim precociousness.

Bobby, who won a university scholarship from a prominent government-linked company and later joined the tech sector, said feelings about not living up to one’s potential as an adult were shared by many of his former GEP classmates.

“I still don’t know what my gift is, after all this time. I do feel special and different, and I think there are parts of me that hew closely to traditional gifts, skills or talents.

“But there are also parts that don’t comport neatly. I wonder how many of my gifts were grown in me as a way of fulfilling the prophecy, because of my belief in it, versus being something truly innate.”

Missing out on the GEP, on the other hand, could be wounding in its own way. My brother, the youngest of three children, said he developed a longstanding inferiority complex from being the only one of us not to make the cut.

He later made up for it by outperforming us in JC and entering one of the world’s top universities, where he is now finishing a master’s degree.

“I think the sting of it was really that the programme marked out a permanent divide between the ‘gifted’ above and the ‘non-gifted’ below,” he said.

“You could work hard and move up the academic ladder, but it sometimes felt like no matter what you did, the peak of your achievements was still lower than the trough of whatever the ‘gifted’ kids were doing. Especially in a country like Singapore, I think that feeling can really eat away at a child.”

Was being “gifted” really that big a deal in the end? Some didn’t think so. Emma, who got into the GEP but decided not to accept the offer, said her parents had made the calculation that it was “better to be a good student in a ‘mid’ school than a lousy student in an ‘atas’ (high class) school”. She is now pursuing a PhD.

“Those of us who rejected it turned out to be just as high-achieving as those who went,” added Emma.

Yet others like Kurt said the GEP shaped a “huge part” of their lives, adding: “Without it, I wouldn’t have had the privilege of attending an ‘atas’ school and making friends with people from more advantaged socio-economic backgrounds.”

I didn’t fully appreciate it at the time, but I think my experiences in the GEP equipped me with research, oral presentation, critical thinking and other useful skills so early on.

By one measure of success, I did win a scholarship to go to university and became a journalist with a reasonably successful start to my career so far.

Would I eventually have matured emotionally, made lasting friendships and performed well if I had remained in my original school? Probably, but it’s hard to really imagine a counterfactual.

Perhaps as a benign side effect, the GEP seems to have created communities and classrooms where the weird kids like me could safely be weird together, and where our mischief and deviance were viewed with more forgiveness and forbearance. And for that, I will always be grateful to have been a part of it.

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

No comments:

Post a Comment