Singapore’s public hospital bed crunch: Are radical solutions needed?

Singapore’s public hospital bed crunch: Are radical solutions needed?

Some patients have waited hours, even days, for a hospital bed. The programme Talking Point hears their stories and finds out that things have got worse since last year as it explores what can be done to ease the problem.

Talking Point host Steven Chia takes a deep dive into Singapore’s public healthcare system.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: For one senior citizen who suffered a seizure, the waiting time for a hospital bed was 38 hours, recounted her daughter.

Another member of the public had a similar story to tell: Her father, having had a fever on and off for three months, went to a public hospital’s accident and emergency (A&E) department. He was admitted after close to 46 hours.

Advertisement

“My dad sat in a chair in A&E for almost two days! (It) was a horrible experience,” said the daughter.

Someone else’s father — who has Parkinson’s disease — was brought to A&E a few times owing to low sodium levels. He was also unable to walk. He had to wait one or two days for a bed.

These are some of the stories Talking Point viewers shared when asked about a problem that has got worse.

Between January and September last year, the median waiting time for a bed in Singapore’s public hospitals was about seven hours. In the same period this year, the waiting time was around seven and a half hours.

Waiting times are calculated based on emergency admissions. The clock starts the moment a decision is made to admit a patient and stops when the patient leaves A&E for the ward.

Advertisement

With the median being 7.5 hours, half of the patients waited longer than that and the other half waited a shorter time.

But with people waiting as long as two days, “we have to use more than just the median” for a more accurate picture of waiting times, said Jason Yap, Vice Dean (Practice) at the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore (NUS).

He proposed looking at the 90th percentile of patients. “If the 90th percentile is reasonable, then it’s (just) the last 10 per cent who have great difficulties,” he said.

While they may be “outliers”, long waits are “not ideal”, he added. “It’s an area that needs to be addressed, and I’m sure more can be done.”

There is no publicly available data, however, on the target waiting time in Singapore’s public hospitals or on how long those 10 per cent of patients are waiting for a bed.

Advertisement

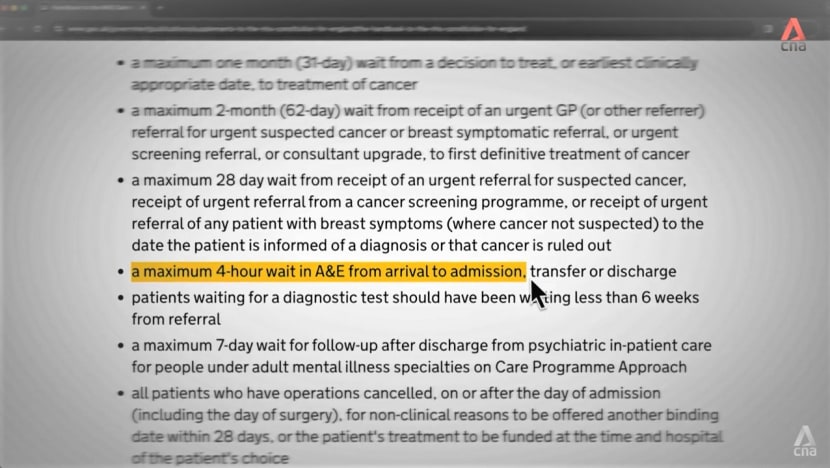

What is known is that the benchmark used in the United Kingdom and the United States is four hours.

In England, 23.1 to 32.9 per cent of patients each month between last November and this April waited more than four hours after the decision to admit was made.

In the US, a study by Yale researchers found that the median waiting time across a national sample of hospitals ranged from around two to 3.4 hours between March and December 2021.

WHY WAITING TIMES ARE LONG

When queried, Singapore’s Ministry of Health (MOH) said the waiting time for beds is dependent on several factors, such as the patient’s condition and the existing patient load in A&E departments.

The public hospitals will triage patients upon their arrival and activate inpatient teams to ensure that patients receive timely care regardless, said a spokesperson.

Advertisement

WATCH: Why some hospital patients wait hours for a bed — What can be done? (22:44)

https://youtu.be/tQ_zwPpyn6c?si=aOYr0r7BVvgQj-Fg

Expanding on the current situation, David Matchar, a professor in Duke-NUS Medical School’s health services and systems research programme, said Singapore’s hospitals are “very much crowded”, so patients must be discharged “before we can fill a very full hospital”.

With a younger population, “inflow equals outflow” and the situation would be “relatively stable”. But as the population ages, older people are “two or three times more likely” to need hospitalisation than younger people.

“We can’t discharge as many (older patients) because … they stay maybe an extra week compared to a younger person,” said Matchar. “We’ve got a much bigger inflow and a smaller outflow, so we get an even worse situation.”

The MOH cited the lingering effects of the pandemic as among the factors that have increased the use of acute hospital beds and “reduced the flow of patients” from A&E departments to the wards.

“Patients who had to defer their elective surgeries during the pandemic are now getting their conditions treated. Planned developments of healthcare infrastructure were also delayed over the last few years,” said its spokesperson.

“In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic increased social isolation among our seniors, which impacted their health. Hence, they tended to require longer periods of inpatient stays.”

Discharging a patient is not necessarily a straightforward process either. Even when someone is medically fit for discharge, there may be circumstances — often beyond the hospital’s control — resulting in prolonged stays, which play a part in the overall waiting time.

“We take (great) pains, actually, to pre-strategise with the patients and their caregivers … to ensure that they’re ready to take the patient home when (he or she is) medically fit,” said National University Hospital (NUH) senior consultant in neurology Jonathan Ong.

But some patients “seem to like to stay in a hospital” longer than they are supposed to. He estimated that there are discharge issues facing around three in 10 NUH patients and/or their family members, “despite a clearly articulated plan”.

“Therefore, sometimes we may have to institute what’s known as an overstayer policy,” he said. This means a patient who is considered to have overstayed is to pay the full hospital rates upon the policy taking effect.

As for medically stable long-stay patients — who are ready for discharge but remain in acute hospitals for more than 21 days — the number has fallen from 230 a week last year to 190 this year on average, stated the MOH.

Yet another challenge in managing beds remains: In Singapore’s public healthcare setting, where 80 to 85 per cent of beds are in heavily subsidised wards, female A&E patients cannot be admitted to open-plan male cubicles and vice versa.

“When you have to segregate by gender, there’ll be some element of sub-optimisation of resources,” said NUH assistant chief operating officer Jeremy Lee.

When the situation calls for more beds, what happens is “we’ll have to park extra trolley beds within the cubicle”, said NUH advanced practice nurse Lucinda Tay.

“So, instead of a nurse (taking) six patients, our nurse will then have to take seven patients.”

The pressure on healthcare workers extends to housekeepers. In NUH, which has more than 1,200 beds and admitted around 67,000 patients last year — one of the highest numbers in the country — its housekeepers must clean 10 to 12 beds daily.

WATCH: I clean a hospital bed for the next patient (and why the long wait times) (7:31)

https://youtu.be/uIJV6OdHnlw?si=jCq7QK3xjbfeO25E

The hospital considers 30 minutes a reasonable time to turn each bed around without compromising cleaning standards. Once a bed is fully disinfected, a new patient may arrive within 10 minutes.

“We have a lot of patients waiting for a bed, so a swift (turnaround) is very vital … to make sure that our patients get timely care and also reduce their waiting time,” said NUH housekeeping operations manager Sai Aung Lin.

ARE MORE BEDS THE SOLUTION?

While NUH is one of Singapore’s largest public hospitals, its patients’ average length of stay hovers around 5.5 days, compared with the national average of seven days, said Lee.

One reason is that it “actively” moves A&E patients to its sister hospitals that are “a little” less crowded. “On average, we move about 10 to 12 patients to Alexandra Hospital, for example,” he cited.

“This helps us decongest (our hospital) and also better manage (the) demands for beds. … This keeps our waiting time more manageable.”

This is just one piece of the puzzle. To ease the bed crunch, more beds can be added — which the MOH is doing, with a target of more than 1,000 additional beds by year end.

For example, the Tan Tock Seng Hospital Integrated Care Hub, which was originally scheduled to open last year, was opened last month. Transitional care facilities for medically stable patients who are finalising their discharge plans have also been set up.

These are part of a five-year plan to add 1,900 public hospital beds to Singapore’s healthcare capacity.

In public acute hospitals, there were 9,820 beds as at last year, with close to 3,600 beds added since 2006 as Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, Ng Teng Fong General Hospital and Sengkang General Hospital opened over the years.

But is adding more beds really the solution? According to Matchar, who has spent more than 35 years working in hospitals and researching how to make them better, “the answer is yes and no”.

To solve the problem of waiting times entirely, possibly up to seven times more beds would be needed over the next 20 years, based on current population projections, he said. “We could potentially keep building more and more hospitals.

But then we might end up with a country that’s filled with hospitals. … And that’s a very inefficient way of taking care of patients’ needs.”

So long as a new hospital has more people being admitted than being discharged, “it’s going to experience the same problem”. Capacity increases must be “balanced with another set of solutions” dealing with the inflows and outflows, he said.

“If we don’t achieve that balance, then we have a mess.”

HOSPITAL AT HOME

One alternative model of care that could help is to treat hospital patients at home instead. The MOH will increase the number of beds in this Mobile Inpatient Care @ Home (MIC@Home) model to between 100 and 200 by year end.

“These (new models of care) will leverage telemedicine and other technologies to right-site patients, while ensuring they receive appropriate care,” said the MOH spokesperson.

As part of MIC@Home, the National University Health System (NUHS) runs NUHS@Home, and up to a third of the patients come directly from A&E without admission to a ward, said Stephanie Ko, the lead clinician for NUHS@Home.

They receive “hospital-level care”: For example, vital signs and oxygen levels are checked, a drip may be set up — procedures in hospital that will be done by nurses. “And that’d be the same in the home setting,” said Ko.

“From a medical perspective, patients will receive exactly the same care at home.”

The medical team visits patients as frequently as their conditions require, usually one to three times a day. This is done in tandem with virtual consultations in the morning.

And patients “pay the same or even less than what they’d pay for staying in a hospital ward”.

Based on studies done by her team, Ko thinks one to two patients out of every 10 in hospital could conceivably receive care at home.

In the three years NUHS@Home has been run, it has cared for more than 3,200 patients, with a cumulative saving of over 23,000 bed-days — the number of days the patients would have had to spend in hospital otherwise — she added.

Travel time to patients’ homes may put some strain on resources, but the NUHS said these visits are part of the medical team’s existing caseload. Health authorities are also assessing how much this service could cost patients going forward.

Can hospitals at home be taken further? Public health specialist Jeremy Lim thinks so and has some ideas for how to do it, chiefly by rethinking the current healthcare business model.

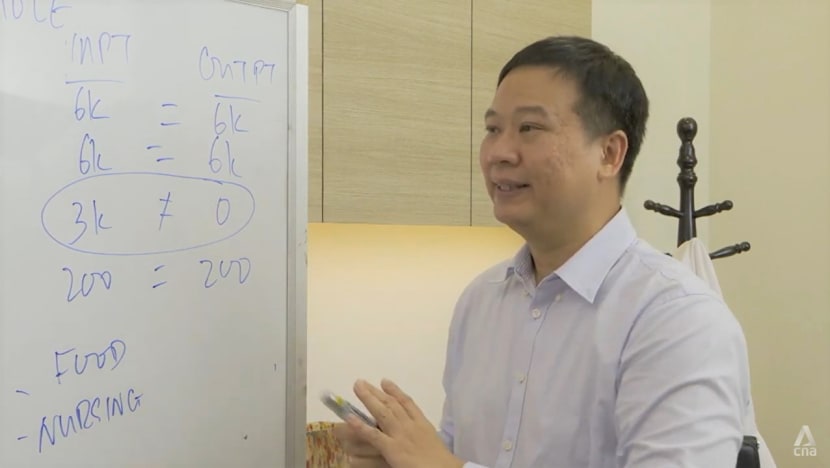

He cited a procedure that more than 1,000 Singaporeans undergo every year: Gall bladder removal by keyhole surgery.

Government and private insurers cover both inpatient stays and day surgeries such as this, but many patients choose to be admitted because of convenience and access to healthcare professionals. Cost is also a factor.

Whether the surgery is done on an inpatient or outpatient basis, the professional fees, such as for the surgeon and the anaesthetist, the facility fee for the operating theatre and the price of the medicines are the same, said Lim.

But when patients have outpatient surgeries, “they and their families will incur some of the costs of food, of basic nursing — someone needs to be with the patient during at least the first 12, 18 hours”.

Hospitals and insurers, meanwhile, save “substantial monies” when there is no inpatient stay. This is why Lim thinks insurers and the state-administered MediShield Life should channel these savings to cover essentials such as food.

“Family leave could be extended,” he added. “First-degree relatives, or even beyond that, can be given time off, mandated under the law, to take care of their family members.

“We have to make it easy for patients and their families to do the right thing.”

He also suggested a “radical” disincentive: “If the standard operating protocol calls for an outpatient procedure, and if patients insist on being retained in the hospital, … perhaps insurance should be tweaked so that some aspect of this isn’t covered.”

While these ideas may require “a whole mindset shift”, as Talking Point host Steven Chia put it, Lim believes the alternatives are unpalatable.

“Do we build hospital after hospital? Do we struggle then with the fiscal tightening, the staffing shortages? Do we want the Goods and Services Tax to move up to 12, 15, 20 per cent?” questioned Lim.

“Every bed-day that we can save allows a more critically ill patient to be in hospital.

“Singapore has to be much more proactive in driving this shift from hospital to home. Because home is the only … ‘infinite resource’ that we have, that can grow with the number of patients.”

Watch this episode of Talking Point here. The programme airs on Channel 5 every Thursday at 9.30pm.

You may also be interested in:

This browser is no longer supported

We know it's a hassle to switch browsers but we want your experience with CNA to be fast, secure and the best it can possibly be.

To continue, upgrade to a supported browser or, for the finest experience, download the mobile app.

Upgraded but still having issues? Contact us

.jpeg?itok=Qe74IJwc)

No comments:

Post a Comment