Height and weight versus height and waist to gauge how healthy you are? Experts weigh in

SINGAPORE – Putting the measuring tape around your middle may be part of a new and more accurate standard to find out if you are obese.

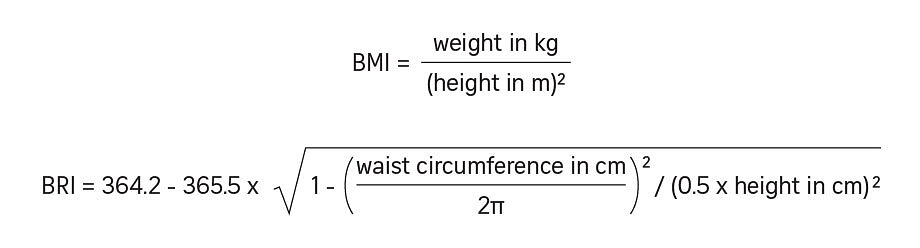

Called the body roundness index or BRI, this new screening method uses waist circumference and height to predict overall body fat and visceral fat levels, instead of using weight and height to measure obesity.

A person with more abdominal and overall fat has a larger waistline and is “rounder” will have a higher BRI score on a scale that ranges from one to 16.

A recent study, published in peer-reviewed journal Jama Network Open in June 2024, found that BRI may be more accurate to estimate obesity and associated its health risks than the standard body mass index (BMI), drawing attention to this potential alternative.

In this study, researchers analysed the BRI of about 33,000 people over 20 years.

They found that a higher BRI was linked with a greater risk of cardiovascular and metabolic disorders, and even cancer.

Abdominal fat, especially visceral fat that surrounds internal organs, is a strong predictor of risks such as heart diseases and diabetes.

For years, BMI has been the benchmark to categorise people as underweight, overweight, obese or extremely obese; and help determine whether they are at risk of certain health conditions; but it has been criticised as flawed.

Created for the Caucasian man, it does not take into account the overall body composition – the percentage of fat and muscle, and bone density – and racial and gender differences.

While some people with a normal BMI can have a high percentage of fat mass and a low muscle mass, others with high BMI may be laden with muscle, which is volumetrically heavier than fat.

Muscle weighs 10 to 20 per cent more than fat because it is denser, so a muscular person and a plump-looking person of the same height and weight can appear quite different in size.

American Olympic rugby player Ilona Maher was recently fat-shamed on social media over her BMI, which at 30 technically puts her on the cusp of obesity.

“BMI doesn’t really tell you what I can do,” she clapped back in an Instagram post. “It doesn’t tell you what I do on the field, how fit I am. It is just a couple of numbers put together. It does not tell you how much muscle I have or anything like that.”

“The BMI works well for most individuals as an indicator of health,” said Dr Tan Hong Chang a senior consultant from the endocrinology department at Singapore General Hospital.

“A person’s weight or amount of body fat becomes a real problem when they suffer from health problems associated with obesity. For health management, no measurement should be considered in isolation.”

He pointed out, however, that BMI, BRI or any form of body measurement cannot differentiate muscle from body fat. “(Athletes) may be heavy because of more muscle mass. They would have a high BMI but normal waist circumference and BRI,” he added.

On what makes BRI a better tool, he said: “Waist circumference will reflect excessive body fat better than weight measurement alone. Most adults gain weight because they gain more fat, and the waist circumference also increases.”

People with a BRI of 6.9 or higher have an almost 50 per cent greater risk of early death compared with those with a BRI of between 4.5 and 5.5, according to Harvard Medical School.

On the other end of the spectrum, those aged 65 and older with very low BRIs of less than 3.4 are at a higher risk of early death linked to malnourishment or a significant medical condition causing weight loss.

Tackling rising obesity in Asia

Professor Yeo Khung Keong, chief executive of the National Heart Centre Singapore, told ST that the paper published in Jama had acknowledged that BRI data is still sparse and has not been sufficiently validated in Asians.

BRI was developed by US researchers in 2013 in response to criticisms of BMI.

“We will need to establish norms for Asians and in larger data sets before we can say BRI is more accurate. I think it is promising for now, but much more work needs to be done”, Prof Yeo said.

He said healthcare professionals still defer to BMI measurement as a default “as BMI is rather unambiguous and is easy to calculate – hence, it remains useful”.

“At the end of the day, healthcare providers and the public should look at multiple measures to provide assessment of metabolic health,” he added.

Metabolic health relates to how well the body maintains normal levels of blood sugar, cholesterol and blood pressure.

This is especially pressing as obesity has become a pandemic in Asia-Pacific, with an alarming rate of increase in its prevalence, he added.

In Singapore, 11.6 per cent of people aged 18 to 74 were considered obese in 2022, compared with 10.5 per cent in 2019/2020.

The US, which has one of the world’s highest prevalence of obesity, 41.9 per cent of adults aged 20 and above were obese in the period of 2017 to March 2020.

Prof Yeo says it is possible to tackle this growing problem efficiently.

“For the longest time, people think that obesity is a mind over matter thing – believing that you can lose weight, and you will lose weight; or believing that you can exercise, and you will start exercising,” he noted.

“Now there are drugs in the market and surgical procedures (such as gastric bypass and gastric banding) that can make an impact on obesity. Frankly, if it makes sense to prescribe these drugs that can result in weight loss and then subsequently better health outcomes, why not?”

Drugs are important for those who are not able to exercise because they are already encumbered by health problems, he said.

However, these drugs should be leveraged as part of the larger healthcare ecosystem that includes policies such as sugar tax to programmes like Singapore’s Nutri-grade scoring system, as well as Healthier SG and Active SG programmes, he added.

“But I am very mindful that we do not want to ‘over-disease’ obesity. The imperative of programmes such as Healthier SG is to stay healthy and avoid developing a chronic medical condition that becomes a lot more challenging to manage, not simply from a cost standpoint, but also from missed opportunities,” Prof Yeo said.

“Perhaps by identifying obesity as a problem, people will recognise that this is something we need to work on, and I think it adds to the overall national narrative on staying healthy.”

Prof Yeo and a group of cardiovascular specialists and other specialists from the Asian Pacific Cardiometabolic Consortium co-wrote a review about obesity and cardiovascular health in the Asia Pacific region from a metabolic angle, looking at factors like diabetes, obesity and high cholesterol. It was published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Asian Pacific Society of Cardiology in June 2024.

“Even though the paper does talk about medical treatment in terms of drugs, weight loss and surgery, I think the conversation should be about staying healthy, having a healthy lifestyle. Prevention is key, as treatment alone cannot reverse the tide of obesity,” he added.

Join ST's WhatsApp Channel and get the latest news and must-reads.

No comments:

Post a Comment