SG • Global

Henry Kissinger on leadership, Lee Kuan Yew and US-China relations

The former US secretary of state is optimistic about global leadership despite a divided world.

Most leaders are managerial, not visionary. But merely managing the status quo isn't the best response to crises. Tough times call for transformational leaders who can transcend the circumstances they inherit, and carry their societies to new heights.

This is the subject of a new book by former United States secretary of state Henry Kissinger, who turned 99 this year.

At over 500 pages long, Leadership: Six Studies In World Strategy identifies six transformational leaders who dominated the second half of the 20th century: former German chancellor Konrad Adenauer, former French president Charles de Gaulle, former US president Richard Nixon (also his former boss), former Egyptian president Anwar Sadat, former Singapore prime minister Lee Kuan Yew and former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher.

Giant from Lilliput

The book's choice of leaders is debatable. The Watergate scandal, for example, has clouded Mr Nixon's legacy even though he steered the US through a time of public hostility towards its foreign entanglements, and worked to achieve a global balance of power for peace.

But all six leaders' lives were shaped by what Dr Kissinger calls the Second Thirty Years War, a period of global conflict from 1914 to 1945. They were born into modest means and challenging national circumstances, and rose on their own merits through academic and military institutions that made such meritocracy possible.

Among them, Singapore's founding prime minister Lee Kuan Yew is singled out for special mention.

Why? Because each of the other leaders represented a major country with a culture formed over centuries, if not millennia.

For such leaders, as they attempt to guide their societies from a familiar past to an evolving future, success is measured by their ability to direct their societies' historical experience and values in order to fulfil their potential.

Mr Lee, however, took charge of a small country that had never before existed, and whose political past was solely as an imperial subject. In fact, Dr Kissinger names one of the chapters "The Giant from Lilliput" in reference to his outsized contributions.

Mr Lee's achievements, notes Dr Kissinger, were to overcome Singapore's early experience to conjure up a dynamic future for an ethnically diverse society, and to transform a poverty-ridden city into a world-class economy.

For Singapore to survive as a nation, its domestic and foreign policy had to be closely intertwined.

There were three requirements: economic growth to sustain the population, sufficient domestic cohesion to permit long-range policies, and a foreign policy nimble enough to survive among international giants as well as neighbours - requirements which have endured till today.

Unlike many post-colonial leaders who sought to strengthen their position by pitting their countries' diverse communities against one another, Mr Lee fostered a sense of national unity out of its conflicting ethnic groups.

He said in a speech in 1967: "It is only when you offer a man - without distinctions based on ethnic, cultural, linguistic and other differences - a chance of belonging to this great human community, that you offer him a peaceful way forward to progress and to a higher level of human life."

US-China relations

The book devotes a whole chapter to Mr Lee's geopolitical preoccupations, in particular, US-China relations which have taken on greater salience amid their sharpening rivalry.

Dr Kissinger says that in Mr Lee's view, the great American qualities of magnanimity and idealism were insufficient on their own, if not balanced by a strategic realism.

Mr Lee feared that the US' tendency towards moralistic foreign policy might turn into neo-isolationism, when faced with "disappointment with the ways of the world" and threats to its perceived exceptionalism.

His approach to China, like his analysis of America, was unsentimental: if the US' challenges lay in its oscillations, the problem posed by China was the resurgence of a traditional imperial pattern.

While Mr Lee respected China's single-minded pursuit of objectives, he felt that the millennia during which it conceived of itself as the Middle Kingdom or central country in the world - and classified others as tributary states - was bound to have left a legacy in Chinese thinking.

He advised Washington not to treat China as an enemy, but to integrate it into the international community and accept China as a big, powerful rising state with a seat in the boardroom.

As for China, he directed some of his appeals to a younger generation who had never experienced the country's tumultuous past, and who might not be aware of the mistakes China had made as a result of hubris and excesses in ideology.

Close friendship

Beyond statecraft, what is particularly satisfying about the book are its anecdotes of the personal friendships Dr Kissinger forged.

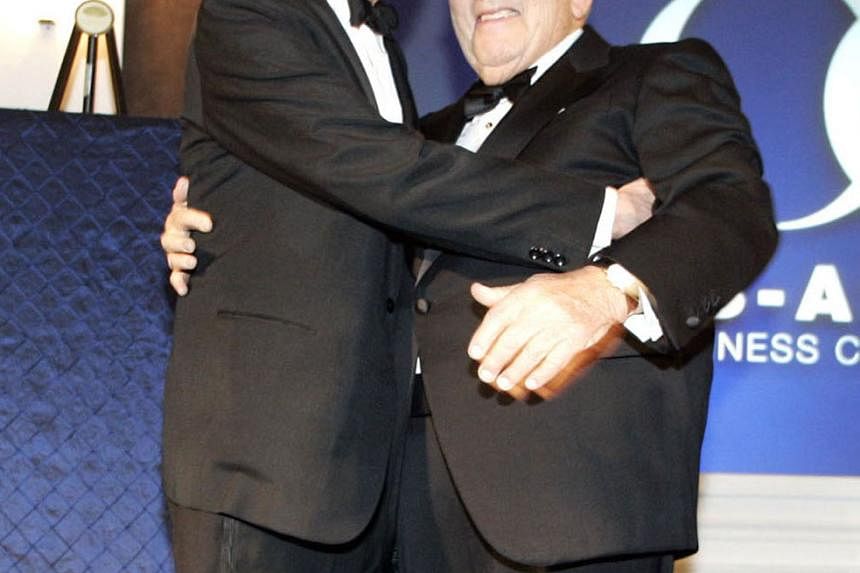

In Mr Lee's case, their friendship came to include another US secretary of state, Mr George Shultz, and Mr Helmut Schmidt, the German chancellor from 1974 to 1982. They met at one another's residences over the years.

Conversations with Mr Lee were a personal vote of confidence, says Dr Kissinger, and signalled an interlocutor's relevance to his otherwise monastically focused existence.

Movingly, he observes Mr Lee's interactions with Mrs Lee after she experienced a stroke in 2008, as he read books to her aloud by her bedside, including Shakespeare's sonnets.

In the months following her death in 2010, Mr Lee took the unprecedented step of initiating several phone conversations with Dr Kissinger, in which he made reference to his grief and specifically to the void left by his wife's passing.

"I asked whether he ever discussed his solitude with his children," writes Dr Kissinger.

"'No', replied Lee, 'as head of the family, it is my duty to support them, not lean on them'."

The book concludes that the six leaders will be remembered for the qualities associated with them, and which defined their impact: Mr Adenauer for his integrity and persistence, General de Gaulle for his determination and historical vision, Mr Nixon for his decisiveness, Mr Sadat for forging peace, Mr Lee for his imagination in founding a new multi-ethnic society, and Mrs Thatcher for her principled leadership and tenacity.

Whether one agrees with their specific policies or not, it is hard to deny that they shared common traits rooted in their backgrounds: a directness and frankness about hard truths, and boldness and willingness to offend entrenched interests if needed.

They also brought together the two fundamental modes of leadership: the "statesman" - that which is pragmatic and managerial - and the "prophet", or the visionary and transformational.

The question is whether such leadership can be sustained in today's divided world. In US-China relations, it has become increasingly difficult to see how two different concepts of national greatness - as Dr Kissinger puts it - can co-exist peacefully.

With the Ukraine war, the challenge is whether Russia can reconcile its view of itself with the self-determination and security of the countries that it has long defined as its near abroad - mostly in Central Asia and Eastern Europe, and to do so as part of an international system rather than by domination.

When the only constant is change, is any leader today really able to conduct long-range policy? Is strong leadership - displaying strength of character, intellect and hardiness - still possible?

The book ends on a cautiously optimistic note. These questions have been asked before, and although it is harder for thoughtful politicians today to swim against the tide of warring ideological tribes, leaders have - and can - emerge who rise to the occasion.

After all, Mr Lee, Mr Sadat and Mrs Thatcher were largely unknown when they came onto the scene. Likewise, few who witnessed the fall of France in 1940 could imagine its renewal under Gen de Gaulle in a career spanning three decades. Yet all were able to, in their own way, shape the present and future, move their societies towards a higher purpose, and rectify some of the shortcomings.

The Stoic philosopher Epictetus wrote: "We cannot choose our external circumstances, but we can always choose how we respond to them." No society can remain great if it loses faith in itself. It is the role of leaders to help guide that choice, inspire their people in its execution, and keep the faith.

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

No comments:

Post a Comment