PM Lee Hsien Loong: A view from up close

He has overcome personal crises and harsh challenges in a journey that has been remarkable.

Irene Ng

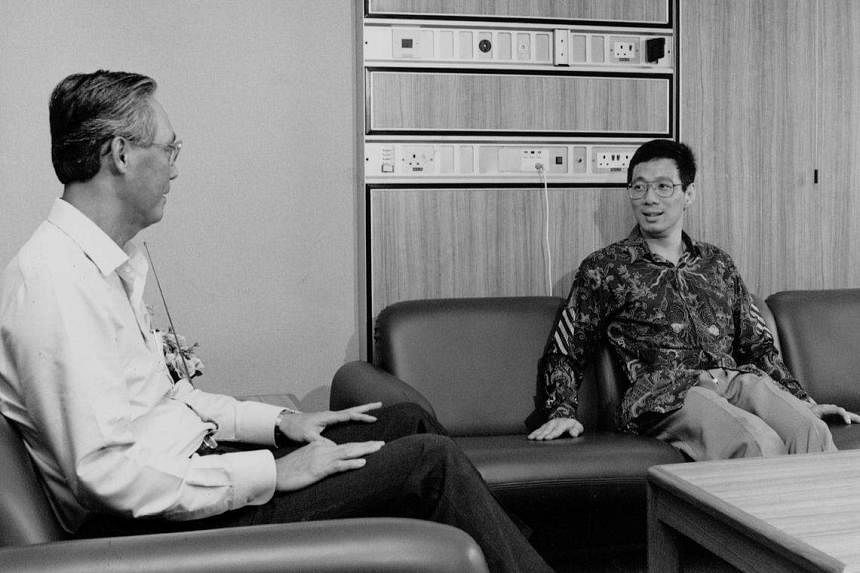

Mr Lee Hsien Loong was battling cancer when I met him at his office in February 1993. He was completely bald, the result of his gruelling rounds of chemotherapy for lymphoma.

He was then Deputy Prime Minister and Trade and Industry Minister. I was a journalist, there to find out how he was coping since his diagnosis in October 1992.

His office, on the 50th floor of the Treasury Building in Shenton Way, was said to give a commanding view of the harbour. Not that day. The curtains were partially drawn, casting the room in shadow. His treatment had made his skin more sensitive to the sun. Other side effects included a weakened immune system, damaged taste buds and nausea.

He had by this time completed five of the six cycles of his chemotherapy, with each cycle lasting three weeks. The drugs were fed through tubes inserted into his chest.

With engaging candour, he described how he adjusted his bathing routine to avoid getting the tubes wet. He obliged when I asked to see the tubes in question, which protruded from a dressing over his chest.

From that day, I saw him as a flesh-and-blood person rather than just a politician. There was vulnerability behind that reassuring smile. There was also courage. He approached these problems with an attitude that said: “I can handle this.”

He was relatively young, at 40. For a leader used to being in charge, this was, in a sense, the hardest part for him – dealing with the unknowns and not being able to exert any control over the outcome. “Such an experience is bound to leave a mark on a person,” he told me without any hint of self-pity. “But I think work goes on, and life goes on.”

He was no stranger to crises. In October 1982, his wife, Mrs Lee Ming Yang, 31, died from a heart attack shortly after giving birth to their second child. Mr Lee was left with a 19-month-old daughter, a three-week-old son, and a broken heart. He told me: “Such things happen. You can’t choose them and you wouldn’t wish them on anybody. You have to live through it.”

I came away from our interview with a lasting impression of a man who personifies the essence of grit and perseverance.

Up till our interview, Mr Lee had not publicly discussed his cancer journey. His first political instinct had been to shore up confidence in the government and to strengthen the leadership ranks. Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong, who had publicly identified him as his successor, observed in November 1992: “To have Loong concerned over a national issue, after being hit by a personal catastrophe, shows a rare strength... He did not fret about himself.”

When Mr Lee was cleared of cancer cells in April 1993, he threw himself back into work. When the Asian financial crisis struck in 1997, he was out there leading the country to a rapid recovery.

The reality was that, while the effects of surviving cancer were profound, at his core, he is who he is – a man completely dedicated to Singapore. And cancer has not changed that. It is a dedication so bone-deep that it is a function not only of thinking, but also being. To understand him, one has to understand the fire from whence the mettle of his character was forged.

Everyone facing a crisis needs courage to get through it. But Mr Lee Hsien Loong the political figure has a form of courage that I believe is more demanding and more exhausting: the courage to bear the collective weight of the present and past, and to focus on the future, however uncertain.

In his political life, most, if not all, of his decisions were thrust upon him, by events beyond his control: financial panics, pandemics, terrorist plots, geopolitical shifts, political scandals involving errant MPs and contentious siblings, and so on. They rarely involved dealing with certainties but probabilities – probabilities of what would happen and what would work. And in the end, he had to deal with the cards he was dealt.

An extraordinary upbringing

Perhaps more than anyone in his cohort, he understood early the pitfalls that came with political service. He grew up in a house in Oxley Road where a group of men had converged to discuss forming a political party and fighting for the independence of Singapore. The range of experiences he was exposed to as a child as he followed his father, founding prime minister Lee Kuan Yew, on his political outings was salutary.

The eldest of two boys and a girl, Mr Lee Hsien Loong was not spared the shocks of political battle. Once during a troubled period in Malaysia in 1965, his father had asked him to look after the family should anything untoward happen to him, the Singapore PM. Mr Lee Hsien Loong was then 13.

After Singapore’s separation from Malaysia, his parents moved out of their home on the advice of the Special Branch to the more secure Changi Cottage, where they stayed for about four months. Their children remained at their Oxley Road house because they had to go to school, which they did with security escort. They visited their parents on weekends. The young Lee’s early exposure to politics gave him a unique understanding of Singapore’s struggle for survival and the sacrifices involved.

The trajectory that delivered him to the Prime Minister’s Office was also unique in some ways.

Few people know that it was Mr S. Rajaratnam, then the Second Deputy Prime Minister, who had, on his own initiative, raised Mr Lee Hsien Loong’s name for consideration at a Cabinet meeting in early 1982 when the issue of political succession was discussed. Mr Goh told me this when I interviewed him for my biography on Mr Rajaratnam, Singapore’s founding foreign minister.

In Mr Goh’s account of that Cabinet meeting, PM Lee Kuan Yew had hesitated, saying that this was his son. No decision was taken on Mr Rajaratnam’s suggestion to approach Mr Lee Hsien Loong for politics. When Mr Goh, then Defence Minister, revisited the matter with the PM in late 1983, the senior Mr Lee said he did not think that his son would accept, given that he had just lost his wife and was trying to get his household in order. At Mr Goh’s persistence, Mr Lee Kuan Yew responded: “You try.” When Mr Goh did in early 1984, the young widower promised to think about it. He came back later and accepted the invitation.

The young Mr Lee, a brigadier-general in the Singapore Armed Forces, was then put through the rigorous selection process that applied to all PAP candidates. This involved being interviewed by two ministerial committees. Mr Rajaratnam stated: “It was I who took the initiative, with the knowledge of the Prime Minister, to request the two committees to consider Hsien Loong as a possible candidate.” He did this, he said, “because I have known him since childhood. His outstanding academic record, his strength of character and his brilliant military career are on record for all to see”.

The first interview was led by former minister Lim Kim San; the second by Mr Rajaratnam. PM Lee Kuan Yew, who had recused himself from the process, was not present at both interviews.

Mr Rajaratnam made the selection process public after Mr Lee Hsien Loong’s entry into politics sparked accusations of nepotism and the emergence of a Lee dynasty. “There is not a ghost of a chance of nepotism, even if it had been attempted, being able to assert itself through these formidable walls of selection procedure,” said Mr Rajaratnam. “Had Hsien Loong been found wanting, he would have been quietly dropped – Prime Minister’s son or not.” Ultimately, Mr Lee Hsien Loong would have to face the electorate and prove himself on the ground. That would be the real test, argued Mr Rajaratnam in the September 1984 issue of the PAP newsletter Petir.

The fact is: When the young Lee decided to join politics in 1984, it was not merely because of who his father was, but because of who he, Mr Lee Hsien Loong, was. In one of his earliest speeches as a politician, in September 1984, he gave a glimpse into his thinking.

Before a person enters politics, he said, he would have weighed the probabilities of success and failure of a political career. “If he succeeds, it may make a difference to thousands of people,” he said, adding: “If he fails, the penalty is a bruised ego and a painful awareness of his limits.” Tellingly, he invoked a quote from Shakespeare’s Macbeth: “But screw your courage to the sticking place and we’ll not fail.”

True to his oath

As one who has observed his leadership closely for many years, I believe that what motivated him to dedicate his life to political service was an appreciation of how special his country was, and an obsession to keep it special, not only for his generation but for future generations.

When he was sworn in as PM in 2004, he took an oath to discharge his duties “to the best of my knowledge and ability, without fear or favour, affection or ill-will”. It is an oath that demands a commitment to meritocracy, democracy, the rule of law and good governance; an oath he took seriously.

Upon taking over the helm, Mr Lee was not popular with those who suspected him of being arrogant and hardline. Indeed, a major question on the minds of many then was whether he could bond with the people and carry them with him.

Today, he is one of the most popular politicians in the country. He is a powerful communicator, able to rally the masses and forge a broad national consensus. Of course, he has his critics. He made mistakes. No leader has left office with a perfect record of success.

Edge of endurance

PM Lee has steered the people through many a crisis, but the most demanding for him personally was perhaps when his father died in 2015. As PM, he bore the responsibility to lead the nation in mourning for its founding leader. Although he was raw with grief, he stood strong because that was what the nation needed.

It was sheer grit that got him through. And meditation. He had taken up meditation when Mrs Lee Ming Yang died. His practice improved with the help of a teacher when he had lymphoma. It was a reflection of his state of mind that, on the morning of March 29, 2015, before the ceremonies for Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s state funeral, he sat next to his father’s coffin lying in state at Parliament House – and meditated.

At times, he must have felt close to the edge of endurance. Such as when, following his father’s death, his siblings denigrated him and his office because he could not – as PM – go along with their desire to fulfil the patriarch’s wish to demolish the Oxley Road house. Mr Lee Kuan Yew would have been devastated had he known that, when he willed his house to Mr Lee Hsien Loong, while making his other two children the executors of his estate, it would lead to a bitter family feud that besmirched his reputation and that of his family, and became fodder for the country’s critics.

PM Lee Hsien Loong recused himself from all government decision-making processes concerning the house, which has historical significance to the country. He also sold the house to his brother, with each donating half its value to charity, thus giving up any personal interest in or influence over its ultimate fate. He had to straddle his positions as PM and a son of Mr Lee Kuan Yew and, again, he placed country over self and family.

At the recent May Day rally, his last as Prime Minister, he radiated the aura of a leader who has given his absolute all. He has, and it showed in his gaunt frame and moist eyes when the audience gave him a standing ovation.

When he bowed deep before them, trying to keep his emotions in check, I remembered that day in 1993 when I got an up-close glimpse of this man that so many today are hailing as an extraordinary leader. He is extraordinary, but it is his humanity that moved me. And moves me still.

- Irene Ng is a former journalist who was a PAP Member of Parliament from 2001 to 2015. She is the authorised biographer of Mr S. Rajaratnam.

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

No comments:

Post a Comment