Kopi, tea and funerary: Why some Singaporeans are talking about death at the dining table

SINGAPORE – It is a warm Thursday night and 49-year-old educator Tan Ming Li is expecting company.

At Indian restaurant Podi & Poriyal in Serangoon Road, the stage has been set for dinner: napkins folded in neat rectangles on tables, the lights dimmed tastefully, the room perfumed with a floral scent.

The conversation, however, is less palatable.

Twenty-six strangers who met mere minutes ago reach into their bags and pull out prized possessions, almost too painful to behold.

Under the gentle yet firm encouragement of Ms Tan, they start to talk about all the things that would in most other circumstances have been banished from the dinner table: death, grief and loss.

One participant smooths out a photo of her late husband, taken two years before his death from brain cancer in 2021. Tears brimming in her eyes, she reflects on their turbulent relationship and bittersweet reconciliation in his final days.

Another shares a video of her 97-year-old grandmother, sprightly despite her advanced age. Still, she worries if each visit will be her last.

But before they grow too comfortable in their groups, the host announces that everyone will be swopping seats and moving to a new table. The idea is to nudge participants out of comfort zones.

“Of course we don’t want them so uncomfortable that they are walking out of the room. It needs to be safe and comfortable enough that they are open to share, yet at the same time fresh enough to push them to talk about things that might be difficult to address with friends,” says Ms Tan, founder of one-year-old local social enterprise The Life Review, which aims to normalise conversations about death, dying and bereavement.

The idea for the two Death Over Dinner sessions she has run so far come from the American non-profit initiative of the same name. And like the original version, which was set up in the United States in 2013, these macabre parties are meant to provide a form of catharsis for the bereaved.

“When you start to sweep the topic of death under the carpet, it becomes a big taboo, which gives it a lot of power.”

Society is deathly afraid of dying, adds Ms Tan, and refusing to confront the ugly but inevitable reality of what lies ahead could preclude reconciling with estranged family members or setting out one’s preferred funeral arrangements.

And in the aftermath, there is the question of how to face the tempest of grief and pain, bottled up within with nowhere to go – a feeling that Ms Tan, who lost her mother to cancer at 17, knows all too well.

“At the time, the only thing my father said to me was, ‘You have to accept it,’” she recalls grimly.

“And that was it. I knew nobody who had lost parents or anyone close, so I accepted it, moved on with my life, went back to school, did everything as though nothing had changed.”

Then came one tragedy after another: the passing of her father, grandmother, aunts and uncles.

“Because there were so many losses along the way, I had this very detached view of relationships. I was worried that if I got too close to someone or something, it was going to disappear.”

Ms Tan, whose day job is teaching mindfulness and yoga, wishes someone had taken the time to sit down with her and process what she was going through. And to spare others the same anguish, she has taken it upon herself to create that space, with the help of food.

“Asians are a bit more reserved,” she says with a knowing smile.

“You can bring a group of people into the room and try to facilitate a conversation, but it’s hard to set them at ease. But when we talk about food, we almost light up, and that becomes the opening that starts a conversation.”

Each of the seven courses at her Death Over Dinner event is preceded by a short explanation of the ingredients included in the dish.

For instance, the chakka biryani is made with baby jackfruit, which, as chief executive Srikiran Raghavan, 49, of Arpanam – the company that owns Podi & Poriyal – explains, is offered to threshold goddesses by women in some southern Indian communities.

Jackfruit wood is also used to construct funeral pyres in certain cultures.

It is an incredibly insightful evening and unlike any other dinner party I have ever experienced. But with tickets starting at $135 a head for a set dinner – the money goes towards supporting The Life Review’s other initiatives, like its end-of-life literacy programme for caregivers – it might not be the most accessible arena to talk about death.

Thankfully, cheaper alternatives exist.

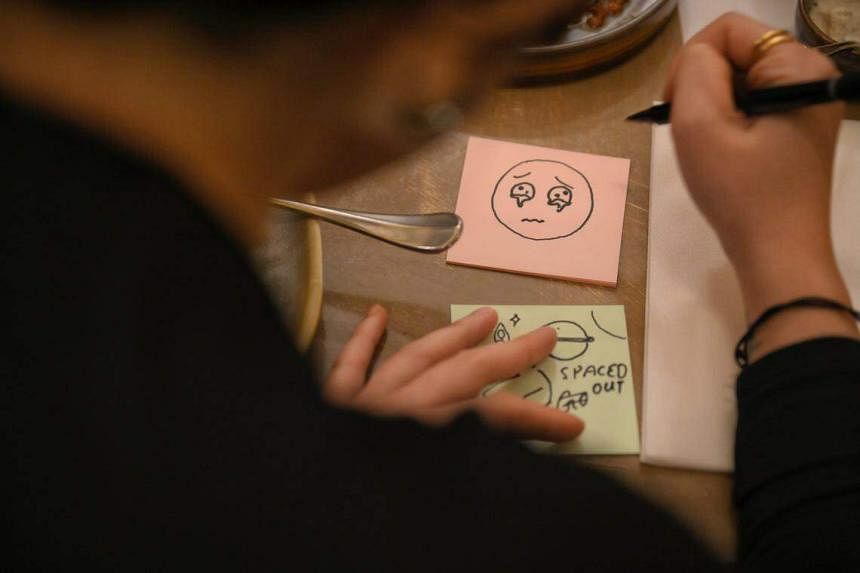

Two weekends before the dinner, I visit a free Death Cafe run by non-profit youth group Ashtronaut.

This, too, is a borrowed concept. From its 2011 genesis in the London home of late founder Jon Underwood, the Death Cafe movement has since spread to 89 countries, reconvened in more than 18,000 gatherings.

The Ashtronaut team, headed by freelance make-up artist Amber Lim, has held nine sessions in Singapore from July 2023. It organises one a month, and alternates between physical and virtual sessions.

Like Ms Tan, Ms Lim, who is in her 30s, was inspired to hold these Death Cafes after her own brush with bereavement.

She lost her mother to illness in 2017, and knows how lonely the silence of grief can be. Social workers could provide her with practical advice and doctors dispensed medical information, but no one gave her the emotional support she craved.

“I wanted to start something for other people going through the same thing,” she tells The Straits Times.

“There is currently a gap in the death literacy of Singaporean youth. And if they are not equipped with the knowledge, they will not be able to help themselves or their parents or grandparents.”

However, it is not just the young who show up to these sessions. At the Death Cafe at Marymount Community Club, I meet a group of about 15 participants from all walks of life – from university students in their early 20s to a 79-year-old retiree.

They come for all sorts of reasons.

Madam Peggy Lim, a 70-year-old retiree, says she was propelled by a kind of necessity. As a volunteer at her church, she often facilitates activities for seniors, which puts her in constant contact with many elderly folk, some of whom are very sick.

“Death is a very imminent possibility for many of the seniors I see, so I want to bring them some comfort and knowledge of what to expect, how to feel comfortable about what’s to come. If not they might be fearful,” she says.

Ms Jocelyn Tan, 29, is a civil servant and nowhere near the age that people typically start planning for the end of life. But that is part of the point – she wants to try to shift the perception of when such preparations should be made.

“I feel like you need to embrace death to live a good life, to live each day with meaning,” she says.

“This place gives me the space to talk about such issues, which my family and friends don’t really like to discuss openly. We usually stick to happier topics, like travel, careers or money.”

Here, conversation takes a more contemplative turn. Over snacks and hot drinks, participants discuss loss and fears about dying in our circle of seven, guided by the steady hand of trained facilitators.

Ms Tan’s Death Over Dinner and Ashtronaut’s Death Cafe sessions build on a steady stream of community efforts to normalise conversations about the end of life.

There is Both Sides, Now, a community project first presented in 2013 and now run by ArtsWok Collaborative, an arts-based community development organisation in Singapore. Through art exhibitions, performances and workshops, it weaves conversations about dying into everyday community life.

Similarly, the Dying To Talk campaign, run by Nanyang Technological University (NTU) students in 2021, encouraged participants to confront mortality with their family members over dinner at home.

That was also the year All Death Matters, a graphic novel commissioned by the Lien Foundation that spotlights palliative care, was released. The foundation played an early role in normalising the conversation around death through booklets and resources.

The Government, too, has been pushing citizens to plan for their final days.

In 2023, the Government launched a national Pre-planning Campaign and announced that certification fees, typically priced between $25 and $300, for Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) applications made at roving booths in Tampines and Queenstown would be waived. It also extended the waiver of the $70 application fee for citizens till end-March 2026.

The LPA allows another person to make decisions on the behalf of the applicant, should he or she lose his or her mental capacity.

Dr Andy Ho, an associate professor at NTU’s School of Social Sciences, says these moves have helped to shift the perception of death in Singapore, with more people now aware of what life’s final journey entails.

But wholly undoing centuries of superstition and taboo will take yet more time, as well as a nationwide campaign that spans multiple fronts.

Apart from educating the young about death processes through formal education, the message needs to be hammered home through billboards, bus advertisements, flyers, pamphlets, commercials, radio programmes, newspaper and magazine articles, social media posts and the like.

“All of these initiatives would help create dialogue among members of the public who are interested. Even for those who may not be interested, their friends who are could invite them along (to death-related events) and get them to open their eyes,” he notes.

He points to Hong Kong as an example of the success of consistent social programming.

In this once-tetraphobic society – the number four is homonymous with the Cantonese word for death – field trips to columbariums have now become a popular activity for many nursing home residents.

Dr Ho also emphasises that as far as possible, these programmes – particularly Death Cafes – should remain free to honour the spirit of openness and accessibility underpinning the original initiative.

Ashtronaut’s Ms Lim has managed to stick to that “no entry fee” principle so far, thanks to a $38,600 grant from the National Youth Council (NYC). The team’s project was picked for its “courage and maturity”, according to Dr Syed Harun Alhabsyi, a panel judge at the agency’s Youth Action Challenge Season 4.

He adds: “It is encouraging to see this project flourish through the support of Youth Action Challenge and it speaks to the value and renewed perspective that ideas from our youth can bring to relevant topics that society may grapple and struggle with today.”

But the future of Ashtronaut’s Death Cafes and its continued source of funding hangs in the balance.

“We’re really quite stretched in terms of manpower. And we don’t have the capacity to bring in more people because we don’t have the resources to train them to carry on these conversations,” says Ms Lim, who churns out monthly programmes with only three core team members – and a roster of ad-hoc volunteers – to help her.

She will also need to find a way to pay for venue rental, food and drinks, as well as marketing collateral. Each session costs her around $1,000 to run.

“We’re still unsure now, but after our funding ends, we might run quarterly instead of monthly events because it’s putting quite a strain on us and our work.”

While the long-term sustainability of this arrangement remains to be seen, Ashtronaut’s collaboration with NYC typifies a partnership that Dr Ho says is key to the effectiveness of public education.

“Having government support is crucial. Yet at the same time, if the people on the ground are not buying into it and don’t implement it well, that could also be a problem,” he says.

“And so meeting in the middle where there’s sufficient top-down support from the government level, and also enough passion and groundwork being built up from the community – that would be the most ideal scenario.”

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

No comments:

Post a Comment