Lunch with Sumiko

Keep calm, watch your thoughts, speech and actions – these are principles Buddhist leader lives by

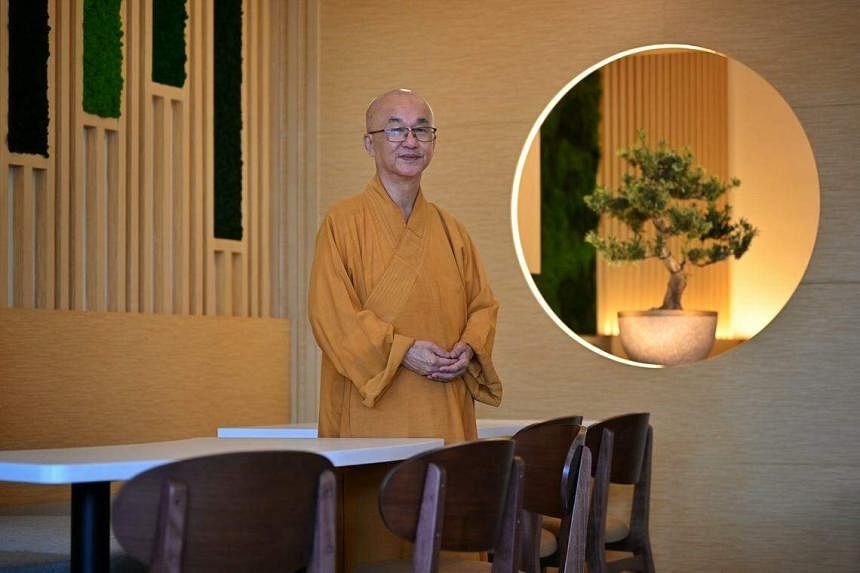

Venerable Seck Kwang Phing has been president of the Singapore Buddhist Federation since 2014. He tells executive editor Sumiko Tan why he decided to be a monk, and how he deals with disgruntled people.

When Venerable Seck Kwang Phing graduated from Nanyang University in 1978, he joined the Immigration Department as an officer.

It quickly dawned on him that he would have to be involved in operations with the police to hunt down illegal immigrants, and that he would have to carry – and possibly use – a gun.

This went against his Buddhist beliefs.

“If the guy had a weapon, I wouldn’t fire at him; I’d fire into the air. Then I’d be a big target,” he recounts with a chuckle.

He asked for a transfer and, because he had a teaching certificate, was posted to be a secondary school teacher.

Two years later, in 1980, he decided to fulfil his dream of becoming a Buddhist monk and was ordained.

In the decades that followed, he headed various temples and taught Buddhism. In 2014, he became president of the Singapore Buddhist Federation.

The federation is the umbrella body for Buddhist monasteries, institutions, monks, nuns and lay Buddhists. It promotes the practice of Buddhism and is involved in community work. It also set up and manages the Maha Bodhi School and Manjusri Secondary School.

Among the activities it is organising ahead of Vesak Day on June 2 is a light offering at Ngee Ann City’s Civic Plaza on May 28.

I’m meeting Ven Kwang Phing at a cafe at Kong Meng San Phor Kark See Monastery in Bright Hill Road, near Bishan.

The peaceful sanctuary sits on a site the size of nearly 11 football fields and houses stately buildings, prayer halls, a pagoda and a columbarium.

The appropriately named Zen Cafe near the reception area is a pleasant space with high ceilings and wood-panelled walls decorated with moss art.

Ven Kwang Phing has chosen to meet at the monastery because his late master was the abbot there, and it was also where he was ordained.

There is another reason. “This is near to your office,” he says, referring to News Centre in Toa Payoh. “You don’t have to run around too much.”

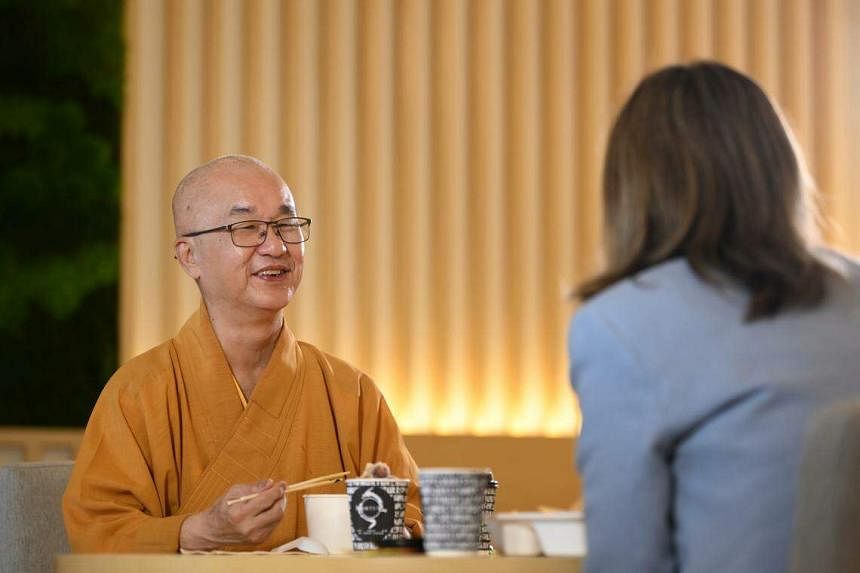

The cafe serves a small selection of vegetarian dishes, breads and pastries. Ven Kwang Phing gets a noodle dish and I decide to try the seafood burger (it is mock calamari). Taro spring rolls sound interesting, and I order one for each of us. He gets a long black coffee and I pick a soya milk.

He tells me he has been trying to cut down on carbohydrates. He often has a very light breakfast of noodles or a salad, and lunch could be brown rice. He usually doesn’t have dinner.

He says that after he was ordained, he did not take dinner for more than nine years. But with a packed work schedule, he found himself sometimes skipping lunch and needing to eat something later.

He told his master that he couldn’t observe the practice of Buddhist monks not eating dinner. “My master said it was excusable; (it was) more important... not to develop an attachment to food.”

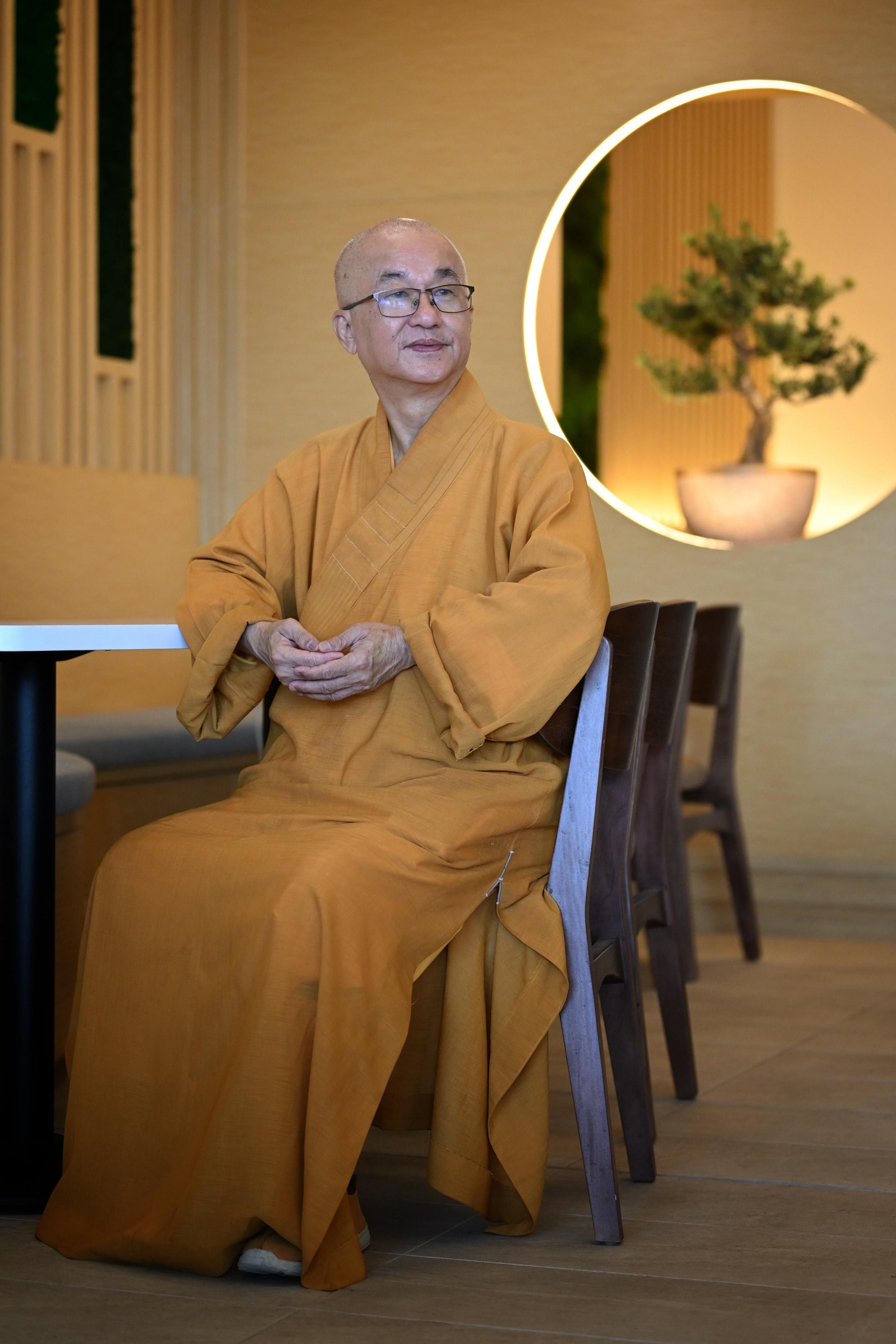

The 70-year-old monk is soft-spoken with a kind, gentle manner. One suspects that there’s also a sense of humour beneath the understated bearing.

Since 2018, he has been the abbot of the Zu-Lin Temple Association in Bukit Batok, which is well known for its 12m-tall bronze statue of Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy.

Ven Kwang Phing was born Lim Hock Hwa in 1953, one of seven children, and grew up in Jalan Hwi Yoh in what is present-day Serangoon North.

“People there planted vegetables and fruit trees. Sometimes, we’d climb up the rambutan trees, or wait for durians to drop from the trees,” he remembers. “It was an enjoyable time, very quiet and calm.”

His father was a principal at Pei Min Public School, a village primary school with three classes in the morning and three in the afternoon. Ven Kwang Phing studied there for a time.

“The teacher told me, ‘If you do something wrong, you will get double the caning because your father will cane you and I will cane you.’ I said, ‘If I score 100 marks, will you give me 200? Should be double, you know, that’s proportional,’” he says with a laugh.

But he never gave any trouble. “I was very guai,” he says, using the Chinese term for obedient.

His parents were religious, and his father helped out at Taoist temple Tou Mu Kung in Upper Serangoon Road. He would tag along. “At that time, there weren’t a lot of educated folk. My father was a principal, so he volunteered to do the paperwork there.”

He attended Upper Serangoon Technical School, and went to National Junior College for half a year before studying at the Teachers’ Training College and passing his A levels as a private candidate.

He had always been interested in poetry. In 1975, he and seven friends in a literary group met poet and artist Tan Swie Hian to seek his advice about a collection of their poems they were publishing.

Besides giving them tips on this, Mr Tan, a devout Buddhist, also spoke to them about Buddhism and meditation. The young Ven Kwang Phing’s interest was piqued.

“We always say that it’s yuan,” he says, referring to the Chinese word for fate. “There was a connection. The time was right.”

He read up about Zen Buddhism and also started practising meditation. “I gained a lot of calmness.”

He joined the Singapore Buddhist Lodge, where he was secretary of the youth section and was involved in many activities. The choir leader at the time was to become Venerable Seck Kwang Sheng, who is the current abbot of Kong Meng San Phor Kark See Monastery, and also vice-president of the Singapore Buddhist Federation.

Early calling

Ven Kwang Phing remembers the moment he wanted to become a monk.

He was then studying at Nanyang University. “One day during dinner, a thought arose in me on how good it would be to enter the monkhood. It is so serene. I can devote my time fully to helping others, and I’d be able to practise my faith without any disturbances and disruptions.”

He resolved to enter the monkhood after his studies, and started making preparations for it even as he entered the working world when he graduated.

After his short stint as an immigration officer, he was posted to Beatty Secondary School, where he taught Chinese studies and geography.

He was introduced by Buddhist friends to Venerable Seck Hong Choon, then abbot of Kong Meng San Phor Kark See Monastery.

The highly respected monk was born in Fujian province in China in 1907 and came to Singapore in the late 1930s. By 1943, he was the abbot of Kong Meng San, which was built around 1920 and started with a single hall surrounded by farm land.

Ven Hong Choon expanded the facilities and was a key figure in the Singapore Buddhist Federation, which was founded in 1949, and the Inter-Religious Organisation (IRO), set up in the same year. He died at the age of 84 in 1990.

The Bright Hill area was still rural when Ven Kwang Phing started his studies under the master. He remembers the long trek there twice a week at night, after work. A small road led to the temple and there was a cemetery nearby.

There were four others in his batch, including Ven Kwang Sheng. The lessons were in Hokkien and Ven Hong Choon was a cheerful presence. “He told a lot of jokes. He cheered everybody up.”

In 1980, after one year of studying the Diamond Sutra, a Mahayana Buddhist text, Ven Kwang Phing left his teaching job and was ordained a monk by his master. He was 26.

The timing was right. His father had by then retired, and a sister he was supporting financially through Nanyang University was just graduating.

She told him: “Brother, now you’re free to go.”

“I said ‘thank you’.”

His other siblings were also supportive (one brother later became a Taoist priest). But his parents, especially his mother, were surprised by his decision. “She couldn’t accept it because she thought she’d lose a son.”

But he told her: “All Buddhists will now be your sons and also daughters. Why must you confine yourself to just one?” He also assured her that he would still be there to help the family if they needed it.

He was given the Buddhist name Kwang Phing by his master. It means “vast” and “virtuous”, and he likes that it is a reminder of how he should lead his life. He says Seck, or Shi in hanyu pinyin, is what monks adopt as a surname as they no longer use their lay names.

After his ordination, he studied at a Buddhist college in Taiwan for 2½ years. When he returned, he was based at Kong Meng San for about five years, where he helped to organise classes.

He moved on to become abbot of Avatamsa Lodge, which was then in Telok Kurau, and also at Kato Lodge in Geylang.

Over the years, Ven Kwang Phing has taught at Buddhist colleges in Penang and also at the Buddhist College of Singapore, which was set up in Kong Meng San Phor Kark See Monastery in 2005.

He became abbot of the Lu-Yin temple in 2018, and also holds positions in other Buddhist organisations and temples, and the Maha Bodhi and Manjusri schools.

Calming the mind

Buddhism is the most popular religion in Singapore, with 31 per cent of residents aged 15 years and above identifying themselves as Buddhists in 2020. This is followed by 19 per cent who are Christians, nearly 16 per cent Muslims, 9 per cent Taoists and 5 per cent Hindus.

There are different schools of Buddhism, and most of the temples in Singapore are Mahayana.

Ven Kwang Phing, who was ordained in the Mahayana tradition, says: “There is only one Buddhism, but the practices can be different. Just like water, whether it is in the vase or in the glass, in the ocean, or in any other container, it remains one water.”

The principles of Buddhism, such as impermanence, remain the same whatever the practice, he adds.

His day starts at around 5am with two hours of meditation. “Once you are calm, you can see things more clearly. With a disturbed mind, your mind is not focused and you may decide wrongly,” he says.

Mornings are a better time to meditate, he adds. “Your mind is refreshed. If you try to meditate after your work, your mind will be full of things and you’ll be trying to clear them.”

He spends the rest of his day on meetings related to the temple as well as the Singapore Buddhist Federation and other bodies he belongs to, including the Presidential Council for Religious Harmony and the IRO.

He also ministers to Buddhists in their final moments. “If I can help others, even a little bit, I do it willingly,” he says simply.

With education levels rising, Buddhists are increasingly seeking to understand more about Buddhism beyond rituals like lighting joss sticks and making offerings, he says.

Rituals also have a place and people seek comfort in them, he notes. “But there are those who are trying to understand what life is, why am I here, how do I live a more meaningful life.”

It is a trend seen in other religions, he adds. “More people are in search of the fundamentals. They want to know the theology, the sutras. For everything you say, you must have a basis, so you have to go back to the precepts.”

He observes that given how common spaces have become more crowded, people are now more impatient and frustrated.

Buddhism preaches tolerance. “We tell our devotees, before you act, you need to consider whether you are giving trouble to others. Before people can complain, are you complaining yourself first?”

His life is guided by Buddha’s teachings, and he says this starts from his thoughts, which translate into what he says and what he does. “So I watch my mind, speech and action, and I make sure it is in line with Buddhist principles.”

It wasn’t something that came naturally, but required training. “Just like you tame a monkey with a banana, it’s about training. Like sportsmen, too, it’s training,” he says serenely.

I wonder how he deals with people who are disgruntled.

He says he will see the situation from the other person’s point of view and try to find a solution to their unhappiness. “If I cannot solve it, I will find someone who can help, a third person whom the person would listen to.”

So do you ever get angry or irritated then, I ask.

He smiles: “Formerly, yes. Nowadays, no.”

We’ve come to the end of lunch and he accommodates the photographer’s request to pose at various spots in the cafe.

He has another interview in the afternoon with a radio station about Vesak Day.

He sees me off at the front porch. “Our interview will not end here. Maybe some time, somewhere, we’ll meet again,” he says as a farewell.

Before this interview is published, I send him several WhatsApp messages to double-check some information. He answers each request promptly and patiently, sometimes with smiley face and folded hands emojis.

I worry that I might be trying his patience with my questions, but feel better when I see what he has put as the description on his WhatsApp profile: Kan po, fang xia, ti qi.

Loosely translated in layman’s terms, it means to look beyond, let go, and move on.

I’m pretty sure he wasn’t irritated by my queries.

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

No comments:

Post a Comment