China’s ‘lobster’ craze: OpenClaw drafts reports, books flights - and raises security concerns

From drafting reports and organising emails to booking flights, artificial intelligence agent OpenClaw has taken China by storm. Despite the excitement, analysts and authorities are warning of security risks.

People attend an OpenClaw installation event near Baidu’s headquarters in Beijing, China on Mar 11, 2026. (Photo: CNA/Hu Chushi)

BEIJING: Across Chinese social media, people are increasingly talking about “raising a lobster”- and sharing what it can do.

The unusual assistant has been drafting reports, organising emails and even booking flights, according to screenshots posted online.

The “lobster” in this case has nothing to do with seafood. It refers to OpenClaw, an open-source artificial intelligence (AI) agent, with the term a nod to its red lobster logo.

OpenClaw has swiftly emerged as one of the latest tech sensations in China, drawing interest from developers, companies and everyday users as the country pushes to harness AI across industries.

There are no official figures on how widely the tool has been adopted. But the enthusiasm has played out both online and offline, with installation tutorials circulating widely and companies organising sessions to help newcomers set up the software.

Analysts say OpenClaw’s rapid uptake reflects strong policy backing for artificial intelligence in China, alongside a tightly integrated tech ecosystem that allows new tools to spread quickly among companies, developers and users.

At the same time, regulators and security experts have warned of potential risks, with authorities reportedly moving to restrict the use of OpenClaw at government agencies and state-owned enterprises.

WHAT IS OPENCLAW?

OpenClaw is essentially an AI agent.

Unlike chatbots such as ChatGPT that primarily answer questions, AI agents are designed to carry out tasks.

With user permission, they can open applications, search for information, compare prices, generate documents and complete multi-step processes with minimal supervision.

OpenClaw was created by Austrian developer Peter Steinberger. Since its November 2025 release, the tool has exploded in popularity.

It is one of the fastest-growing projects in the history of GitHub, the world's most widely adopted AI-powered developer platform. Steinberger himself was hired by OpenAI last month.

Interest in AI agents has been growing globally. Developer meetups in cities such as New York and San Francisco have drawn crowds experimenting with similar software.

In Singapore, a recent OpenClaw community meetup drew more than 500 attendees. Organisers said it was the largest turnout for an open-source project meetup in the country.

WHY CHINA IS MOVING SO FAST

But in China, the scale and speed of adoption have stood out.

Major companies have hosted OpenClaw installation sessions. Tech giant Tencent did so earlier this month at its Shenzhen headquarters, drawing long queues.

Lengthy lines were likewise observed near Baidu’s headquarters in Beijing on Wednesday (Mar 11), when about 1,000 people turned up to a similar installation session hosted by the company.

The three-hour event drew a steady stream of visitors. Many arrived with laptops in hand, others held lobster plush toys won from a claw machine set up by organisers. The event - originally intended for internal staff - also attracted nearby office workers as well as employees’ family members and friends.

Chinese cloud providers have also rolled out simplified deployment tools while installation tutorials circulate online.

Local governments have moved quickly to support the trend. Districts in Shenzhen and Wuxi have unveiled draft measures to support an OpenClaw-centred ecosystem.

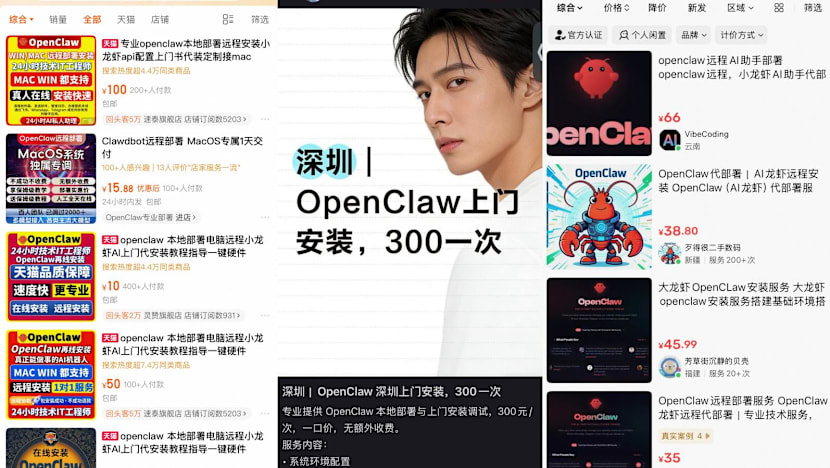

Small side businesses have even surfaced. Checks by CNA on platforms such as Xianyu and Xiaohongshu found listings advertising OpenClaw installation - and even removal - services, with remote or in-home help priced between 20 yuan (US$2.90) and 299 yuan.

Users CNA spoke to cited accessibility as part of the appeal.

While installation is free, running OpenClaw typically requires a cloud server, which can cost as little as 99 yuan a year on some Chinese cloud computing platforms.

Yan Cong, a 35-year-old technology blogger and brand director at a smart home company, said he has been experimenting with OpenClaw to help write scripts, prepare work reports and research health information.

“The most useful feature so far is ‘skills’,” he told CNA, referring to plugins that instruct the AI agent to perform specialised tasks.

“Efficiency gains are undeniable, but the premise is that you must understand your workflow very well.”

Yet for many users, the technology remains experimental.

Chen Ze, 30, a public relations professional, said he first became curious about OpenClaw after watching livestream footage of people lining up outside Tencent’s headquarters to install the software.

“At the beginning, I didn’t have a specific idea of what I wanted it to do,” he said. “I wanted to experience it first and understand how it works.”

At the Mar 11 Baidu OpenClaw installation session, Li, a 34-year-old employee at a nearby technology firm who gave only her surname, said she came to learn more about the tool.

“I wanted to see what the hype was about,” she told CNA.

Jacob Chen, a 25-year-old Baidu advertising employee, said he had been curious about OpenClaw but had not installed it himself because the process can be complicated.

“It’s easier to come here and let the engineers help set it up,” he said.

Analysts said China’s policy signals have helped accelerate the trend.

At the Two Sessions political meetings, policymakers highlighted artificial intelligence as a top priority for economic development, detailing its job-creating and productivity potential.

The government work report specifically called for faster application of AI agents as part of efforts to create new forms of “smart economy”.

In China, once a technology gains momentum, companies and local governments often move quickly to build ecosystems around it - especially when it aligns with national priorities.

Furthermore, the structure of the country’s technology industry is a likely factor behind the quick embrace of AI agents like OpenClaw, analysts said.

“The Chinese tech ecosystem is more vertically integrated,” said Lionel Sim, founder of AI research firm The AI Capitol.

“Companies like Alibaba, Tencent and Baidu own the cloud, the models and the distribution platforms. That means they can ship agent infrastructure end to end without waiting on third parties,” he told CNA.

This integration allows companies to move quickly from experimentation to deployment, lowering the technical barriers for users, Sim added.

China’s “super app” ecosystem could also make tools like AI agents easier to deploy, said Alex Kot, a professor at Shenzhen MSU-BIT University.

He highlighted how platforms like WeChat already integrate messaging, payments and mini programmes, allowing automation tools to carry out tasks across multiple services.

Additionally, after rapid progress in developing large language models, attention may now be shifting toward applications that deliver tangible productivity gains, experts suggested.

Chinese technology firms are already racing to develop their own versions of OpenClaw. AI startups such as Zhipu and Moonshot AI have begun rolling out rival AI agent tools to capture growing demand for automated digital assistants.

“Chatbots were helpful for drafting or answering questions, but the human still had to drive the workflow,” said Ma Rui, a Chinese technology investor and analyst based in San Francisco.

“If AI can actually complete digital work rather than just assist with it, individuals and small teams can automate workflows that previously required several people,” she told CNA.

THE UNCERTAIN ROAD AHEAD

Despite the excitement and hype, experts cautioned that the technology is still evolving, with concerns over security, reliability and potential misuse.

OpenClaw has already been flagged by developers and security researchers for potential vulnerabilities.

Because the system allows users to install third-party “skills” that extend the agent's capabilities, poorly designed or malicious tools could expose sensitive data or perform unintended actions.

OpenClaw may also require high-level device access privileges to carry out certain tasks autonomously, raising the risk of unauthorised system access or data exposure.

China’s National Computer Network Emergency Response Technical Team/Coordination Center issued a security advisory on Mar 10 warning that improper installation or use of OpenClaw could expose users to cybersecurity risks.

That same day, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology warned that default or improper OpenClaw configurations could expose systems to cyberattacks or data leaks.

Chinese government agencies and state-owned enterprises, including major banks, received notices in recent days warning them against installing OpenClaw on office devices for security reasons, Bloomberg reported on Wednesday, citing people familiar with the matter.

Sim from The AI Capitol said the real signal of the technology’s impact will come when companies begin reporting measurable productivity gains or improved customer engagement.

Kot from Shenzhen MSU-BIT University said the technology’s potential remains significant.

“AI agents provide an excellent platform for improving the efficiency of many of our daily tasks,” he said.

Sign up for our newsletters

Get our pick of top stories and thought-provoking articles in your inbox

Subscribe here