Time to go beyond psychiatric focus to address issue of suicide

We need to take into account social, economic and cultural factors as well for a more effective suicide prevention strategy.

Anthea Ong, Jared Ng and Rayner Tan

A short but ground-breaking video may have slipped under the radar during the 2024 National Day Parade: A social worker shared about losing a friend to suicide during his school days. It moved him to work in the mental health field to save others.

His shared story was ground-breaking as suicide prevention in Singapore is often not adequately addressed because of stigma. As well, there is a lack of awareness that suicide is a major public health problem.

In Singapore, suicide prevention efforts have predominantly adopted a medical or psychiatric perspective with mental health services often seen as the primary solution.

However, to effectively prevent suicide, the underlying social, economic and cultural factors that contribute to suicidal behaviour also need to be addressed. This includes tackling issues such as social isolation – for example, studies found that our elderly are getting lonelier – as well as financial stress and cultural stigma surrounding mental health.

Not all individuals who die by suicide have a diagnosable mental illness. Nor is every person living with a mental health condition suicidal. Hence, while psychiatric support is crucial in addressing immediate crises and providing ongoing treatment, it alone cannot fully address the issue of suicide prevention.

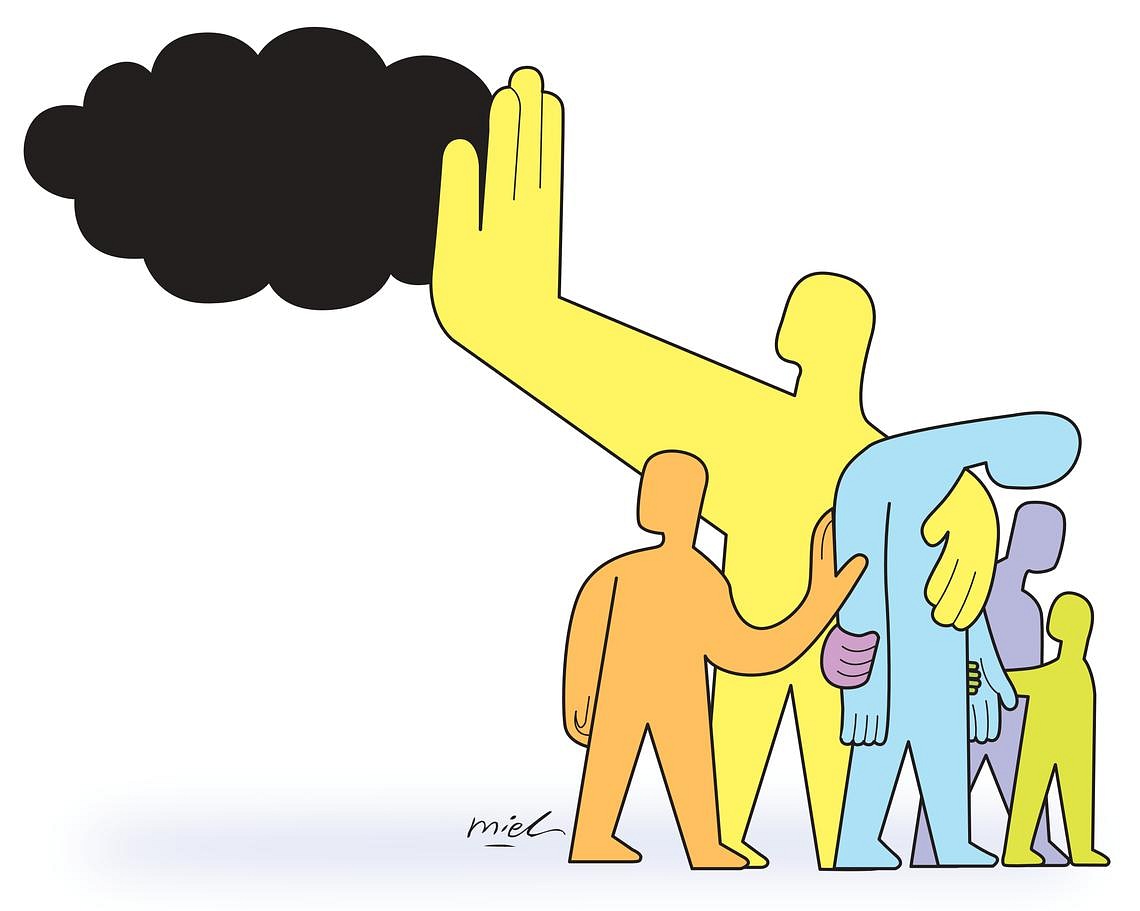

A comprehensive suicide prevention strategy must integrate these broader aspects, creating a holistic approach that encompasses community support, public education and policy changes alongside medical treatment.

Understanding complex nature of suicide

There were 322 suicides in 2023 – a substantial decrease from 476 in the previous year. While this decline is heartening, it is crucial to understand the complex and multifaceted nature of suicide, often described as a “wicked problem”. Each suicide represents a profound personal and societal tragedy.

Wicked problems, by definition, are difficult or seemingly impossible to solve due to their complex and interconnected nature. Suicide intertwines psychological, medical, social, economic and cultural factors. Addressing suicide requires a nuanced understanding of this and an approach that goes beyond individual treatment to include societal changes and support systems.

The reduction in suicide numbers in 2023 should not lead to complacency. Studies suggest that for every suicide, about 135 people are affected, requiring clinical services or support. By this estimate, nearly 50,000 individuals were impacted by suicides in Singapore in 2023.

This number might even be conservative, considering the wide-reaching influence of a single suicide on family, friends, classmates, colleagues and online communities.

Some reports credit the reduction in suicide rates in 2023 to the substantial efforts of cross-sectoral agencies, ranging from hospitals to social service organisations, but this is difficult to prove. Preventive measures often require long periods to manifest tangible results. This complexity underscores the need for a long-term commitment to continuous improvement and adaptation in our suicide prevention strategies.

In addition, it is important to note that according to the Attorney-General’s Chambers, a classification of “suicide” only occurs when there is clear evidence of suicidal intent and self harm. We understand from suicide-bereaved parents that the cause of death is sometimes categorised as “fall from a high place” or “unnatural death”. In addition, estimates from the World Health Organisation (WHO) show that for each person who dies by suicide, more than 20 others attempt it.

Other essentials for prevention

Community-based programmes that promote social integration and fortitude can also play a significant role in prevention efforts.

Another critical aspect is the implementation of early intervention programmes. Training educators, first responders and community leaders to recognise the early signs of distress and suicidal behaviour is important.

Schools and workplaces should be equipped with resources and trained personnel to provide immediate assistance to those in need. Studies found that our young people are reporting higher levels of social isolation and loneliness, with those between 21 and 34 having a higher loneliness score. These factors can elevate the risk of suicide. Between 2021 and 2023, the highest number of suicides was among people in their 20s.

As well, improving access to mental health services is paramount. Reducing barriers to care, such as cost, stigma and lack of awareness, can ensure that individuals receive the help they need before reaching a crisis point. Integrating mental health services and community-based programmes with primary healthcare is one of the ways to enhance accessibility.

Improving access to care must also includes allowing individuals with a history of suicide attempts access to health insurance. Denying them coverage not only increases their financial strain, but also restricts their access to essential mental health care.

Additionally, it is crucial to provide ongoing support and post-vention (post-suicide intervention) for the affected family and friends, as well as survivors of suicide attempts. This could include counselling, support groups and other resources to help them cope with their loss and trauma, reducing the risk of further emotional distress and potential suicides.

“I have been witness to a suicide, I have lost a friend to suicide, and I struggle with suicidal ideation. It cost me my university education, landed me in tens of thousands of debt, and left me with little means to earn enough to pay back my study loan and survive on my own. I will likely never be able to earn more than $1,000 a month, and will likely take my life rather than die of other causes in the near future.”

This was the sad account of one of the 400 respondents to a public consultation in 2020 by SG Mental Health Matters, a ground-up initiative seeking to educate the public on mental health policies. We are part of this diverse community group which includes mental health practitioners, public health researchers, government agencies and advocates with lived experience.

Together, we are co-leading Project Hayat (“life” in Malay) – a White Paper on a national suicide prevention strategy which will be launched on World Suicide Prevention Day, Sept 10, at the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore.

Taking a holistic approach

Project Hayat sees suicide prevention as a multi-sectoral collaboration, ideally led by the Government.

One of the recommendations in the paper, informed by the numerous interviews that we conducted with representatives from countries with national suicide prevention strategies, is the establishment of a national office for suicide prevention to centralise efforts and ensure a cohesive strategy. This office should function independently of mental health services, recognising that while mental health is a critical component, suicide prevention encompasses a broader spectrum of social, educational and cultural initiatives.

Our focus group discussions in Singapore also found that enhancing public awareness and education about suicide is essential for a national suicide prevention strategy. Destigmatising mental health issues and encouraging open conversations can create an environment where individuals feel comfortable seeking help.

Research and data collection are vital for understanding the evolving dynamics of suicide and the effectiveness of prevention strategies. Continuous evaluation of programmes and policies can identify areas for improvement and guide future initiatives.

Along those lines, SG Mental Health Matters’ Project Hayat team is also conducting an online public survey for Singaporeans and residents to participate in the national conversation on suicide prevention.

Suicide remains a wicked problem that demands a multifaceted and collaborative approach. Findings from global studies have shown government-led suicide prevention strategies to significantly reduce suicide rates, particularly among vulnerable groups like the youth and elderly.

By engaging diverse community stakeholders and implementing comprehensive prevention strategies, the way forward for Singapore must be one where every life is valued and saved.

- Anthea Ong is a former Nominated Member of Parliament and a social entrepreneur. Dr Jared Ng is a psychiatrist and medical director of Connections MindHealth. Dr Rayner Tan is assistant professor at the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health at the National University of Singapore. The authors are all members of SG Mental Health Matters.

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

No comments:

Post a Comment