Why many won’t admit they took the direct school admission route

Direct school admissions are becoming more popular but many students still measure their worth through their academic grades.

It is news worth celebrating – more pupils are opting for the Direct School Admission (DSA) route, to secure their secondary school berth based on their unique abilities in areas such as sports or arts, as well as academic subjects like science and mathematics.

The Straits Times reported on Sept 1 that in 2024, a record number of 16,000 Primary 6 pupils applied to be considered for admission through the scheme. Many of these pupils had submitted two or three applications each, with the total number of applications reaching 42,500.

This is heartening news on the face of it, especially since the Ministry of Education in recent years has tweaked its policies and schemes to open up more pathways, including the DSA, for more students to discover and hone their unique talents and interests.

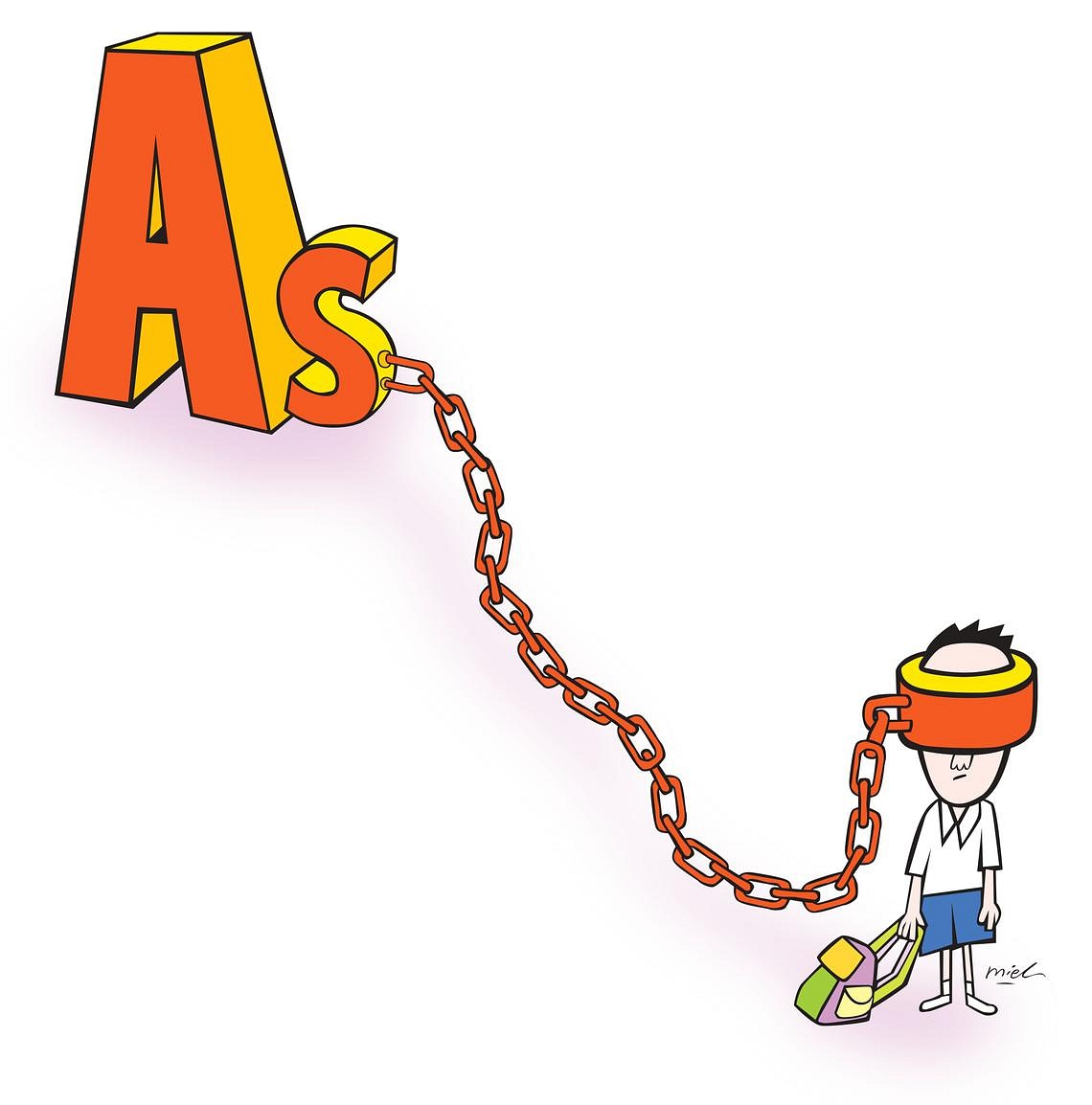

But beneath the hype lurks a more sober reality. The typical Singaporean mindset still values academic grades above all else, which is why many who qualify through the DSA route want to hide the fact. Many don’t want to admit they didn’t meet the academic mark for admission.

Once again this underscores the need to “reset” and change mindsets.

Interestingly, the DSA scheme, which was introduced in 2004, was previously criticised for giving academically bright pupils early entry to choice secondary schools. Some, like MP Denise Phua (Jalan Besar GRC), had also repeatedly raised concerns over children from more affluent families being groomed to enter top schools via DSA, through sports coaching, music classes and interview preparation.

The concerns were partly addressed through a series of changes introduced by MOE beginning in 2018, where all schools were allowed to take in more students and to select applicants based on a wider range of talents.

Schools stopped using general academic ability tests and instead selected students on their strengths in specific academic domains, such as maths and science.

In areas such as sports and the arts, the selection process for the scheme has also been refined to spot talent, even in those who have not had the chance to showcase it yet. There is less emphasis on the awards a pupil has won and more on innate ability.

As MOE said, no doubt the changes have led to an increase in applications and students winning a berth in secondary schools of their choice through the DSA scheme.

Hushing it up

Still, I don’t expect many students, especially those in the top secondary schools, admitting to having won a place through the DSA route.

This has been the experience of many education reporters who have, over the years, tried to profile students who took the DSA route to secondary schools, especially the most selective Integrated Programme (IP) schools such as Raffles Institution and Hwa Chong Institution.

The secondary schools which include the six-year IP admit students with top PSLE aggregate scores – usually nine and below. But the schools also use the DSA to take in a fair number of students who have impressed them with their talent and potential in non-academic areas. This includes a range of sports, be it athletics, swimming or team sports such as rugby. They also admit many students who have shown that they have the potential to make a mark in areas such as debates, public speaking and leadership.

But sadly, when the media, including The Straits Times, reaches out to feature students admitted through the DSA, they tend to shy away.

One mother was surprised when her son, who was admitted to RI, refused to be featured in ST. When she probed him she learnt that her son’s classmates did not know that he had won a place in RI through DSA.

Although he had scored very close to the cut-off aggregate score for RI, the boy told his mother that he would never want his classmates to find out that he entered the school through DSA, which he called “the back door”.

The woman said that her son, who is now doing full-time national service, was miserable throughout his six years at the school, as he focused more on the academics to “keep up and prove himself to his schoolmates”.

Said the mother: “I had encouraged him to try the DSA route to RI, as he showed a lot of interest in his co-curricular activities in primary school, and I wanted him to develop himself in other ways. Little did I know that he will become obsessed with hiding the fact that he entered through DSA. He was miserable trying to keep up with his classmates and chasing all As for the A-levels.”

I have spoken to other young people who had turned down requests for interviews, including some from the National University of Singapore (NUS), who had won a place through the aptitude-based admission scheme which, similar to DSA, takes into account achievements outside applicants’ examination grades.

Laudably, all six universities had broadened their admission criteria over the years to look beyond grades and to signal to applicants that they value their achievements in other areas, whether it is in sports, arts, entrepreneurship or community involvement.

But many university students too turned down interview requests, as they did not want their course mates or professors to know that they didn’t quite meet the entry score for the course of their choice.

Another NUS law student, whose father was a lawyer, went as far as to say that his father would sue my newspaper for defamation if I were to mention him in my article.

What struck me in my conversations with the students was how they tended to measure their worth through their academic grades.

The NUS law student did not want me to mention that he had a “C” for his A levels, and the students from top IP schools did not want me to reveal their PSLE aggregate scores, even though I had promised not to mention the exact score, just that they had fallen short by a few points.

Still, it is heartening that more tweaks to DSA are on the cards as, on Aug 22, Education Minister Chan Chun Sing said MOE was thinking about another review of DSA to make the scheme more accessible to the broad swathe of students, and not just those from families with more resources.

Need to change mindsets

Mr Chan’s announcement is not surprising considering the “resets” in many government policies and schemes announced by Prime Minister Lawrence Wong in his maiden National Day Rally speech in August.

In education, one major “reset” Mr Wong announced was that after 40 years, the Gifted Education Programme (GEP), which caters to the top 1 per cent of primary school pupils, will be discontinued in its current form and replaced with an updated approach to benefit more children. All primary schools will be equipped to identify their own high-ability pupils and run programmes for them.

PM Wong said he wants to build a Singapore where people thrive on their own terms, in ways that are less prescribed and determined; and where people support one another. But several times during his speech, the Prime Minister stressed the need for mindset shifts in order for real change to take effect. “Realising our new ambitions will require a major reset – a major reset in policies, to be sure; but also a reset in our attitudes,” he said.

Indeed, he said, as with many things in education, the shift to a more holistic education will not happen unless parents and students “reset” their beliefs and values in education.

One of the shifts we require is on our obsession with the value of examinations and grades.

I recall MOE’s announcement a few years ago that it would replace exams for children in lower primary with bite-sized forms of assessment. Some parents panicked and began buying up the soon-to-be-defunct exam papers of top primary schools. Since then MOE has done away with mid-year exams for all primary and secondary school levels but parents have turned to tuition centres to conduct mock exams for their children.

There were similar reactions when MOE revealed the details of the new Primary School Leaving Examination scoring system.

It was a good move to phase out the PSLE T-score, where each pupil is compared with his or her peers and assigned a score.

Under the new system which came into effect in 2021, each pupil will be given a score based on how well he or she has done in the subject, independent of how others fare.

But several parents interviewed after the announcement said they now fear there will be even more competition for places in the top secondary schools and they will now target to reach the PSLE score of four.

Singapore cannot continue on this path, especially with the profound changes our youth will face in the workplace with the advent of artificial intelligence.

If this narrow focus on grades and examinations continues, it would churn out students who excel in exams but who lack the competencies to take on jobs of the future. Chasing grades will leave little time for our youth to build competencies such as creativity, adaptability and ability to collaborate with people.

The bold transformation of the education system will need the collective will and action of parents, employers and students.

MOE must continue to “reset” policies that stand in the way.

Parents and teachers will need to help young people discover their unique strengths and interests, and build on them.

Too many employers still hire based on qualifications. They need to look at the skills that their workers bring to the table and develop their potential, if they want them to help grow the business.

And young people too must give up their obsession with grades. Instead, they must seize the various opportunities presented by new and diverse pathways in education to go as far as they want.

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

No comments:

Post a Comment